September 2009 – Volume 13, Number 2

| Title | |

| Creator/owner | Twitter, Inc. |

| Contact Information | http://www.twitter.com |

| Type of product | Short messaging service for various devices |

| Platform | Web, mobile phone, instant messaging |

| Minimum hardware requirement |

Computer with Internet connection or mobile phone/device |

| Supplementary software |

None needed; free applications available online |

| Price | Free; text messaging fees may apply when used on mobile devices |

Twittermania and a Nobel Peace Prize?

Is there anyone who does not know what Twitter is by now? The software service with its chirpy little bluebird logo has become a celebrity in its own right this year, a ubiquitous presence in news broadcasts, political campaigns, entertainment, sports, professional activities, and online sites of every sort. Twitter even made the cover of Time magazine in June of 2009, teamed up with its red carpet pal, the iPhone. This was just prior to the spontaneous use of Twitter by Iranian civilians as they took to the streets to protest government corruption, cleverly using the software to broadcast their cause worldwide. For this role in support of democracy, Twitter, a simple messaging interface, was suggested as a possible candidate for the Nobel Peace Prize (Pfeifle, 2009). There is certainly power in the interaction of technologies and their users, especially when affordances and social needs meet in unforeseen new ways. The question here is whether Twitter has something to offer that might also be powerful for learning, specifically, for teachers and students of English as a Second Language.

Figure 1. Time magazine cover story on how Twitter is changing the way we live

How Twitter is Used

For those few still not familiar with Twitter, it is what is known as a microblogging software platform. It was designed to allow people to send updates to friends and others in answer to the question “What are you doing?” The “micro” prefix refers to the fact that Twitter messages, or tweets, are limited to 140 characters. Twitter accounts are free and are set up online. Users can send updates from the web, from a cell phone, or from other mobile devices that support text messaging. Twitter allows posting of images and website URLs. Unlike an email message, a tweet goes out to the wide audience of the “Twitterverse”; in fact a public tweet can potentially be seen by as many as 3,984,101 people, the approximate number of public Twitter users worldwide (Pantanacce, 2009).

However, it is more likely that tweets will be read by far fewer users since the other important feature of Twitter, choosing which people to follow, reduces the user’s timeline (stream) of tweets to a much more manageable level. By clicking on another user’s account name, you are taken to their home page. If you then click on the follow button, that user’s posts become visible on your own account timeline and if desired, on your mobile device (this is a setting from your home page). In this way, each user creates a personal virtual network based on interest and intent. There are a number of ways to find people to follow. Within Twitter, a user can search by keyword to find another user by name, by profession or interest (which may or may not be listed in a user’s profile), or by location. A more random approach might be to view the Twitter public timeline of tweets or view Twittervision to see tweets as they are posted, superimposed against the backdrop of an ever-shifting map of the world.

Using the @ sign followed by a person’s Twitter name, a tweet can be sent directly to anyone a user is following. This is not a private message, but it is archived in both the sender and user accounts. This is an important feature for language learners in particular because this is what enables conversational use of Twitter.

Figure 2. View of my Twitter homepage

Once a network of followers has been created, the user determines how to deal with the information flow, how often to read tweets and what and when to post. While as many as half of those who set up accounts on Twitter may in fact never adopt it as a communication tool (Grosseck & Holotescu, 2008), some Twitter power users keep up with their Twitter network by subscribing to people’s RSS Twitter feeds or by using a Twitter application that chimes alerts when new tweets are received. Tweetdeck is an example of this type that also allows the user to organize the people they follow into groups, allowing for more efficient scanning of tweets. For a teacher using Twitter with a class, this application would facilitate keeping student messages grouped together and separate from perhaps professional or personal messages. In this example, I have grouped ESL teachers, Techies, Favorites and Friends.

Figure 3. Image of Tweetdeck with several columns of groups

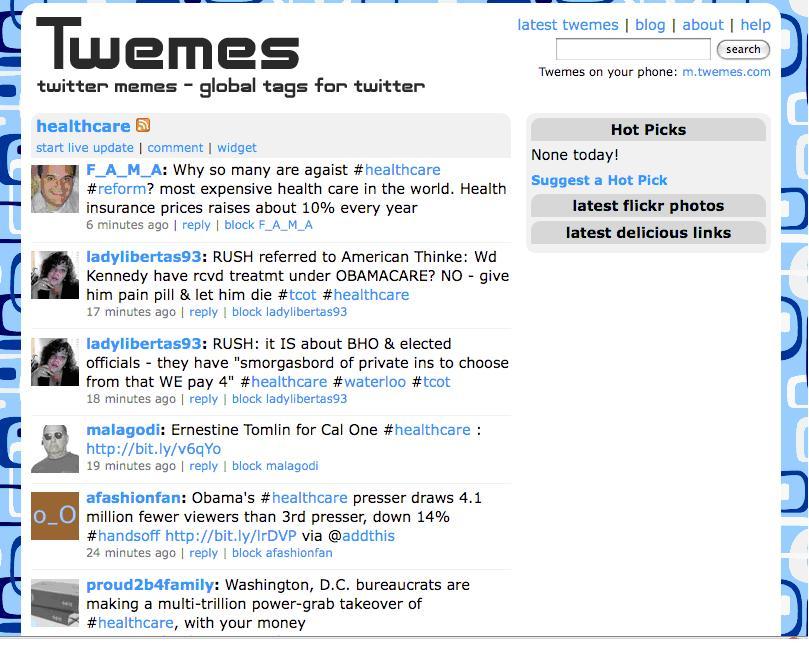

Twitter’s meteoric rise has led to an explosion of applications developed to tweak use of the software according to the user’s needs. There are too many of these to mention here, but Vance Stevens’ June 2008 article on Twitter for TESL-EJ provides a fairly comprehensive list. There are two applications that do have particular relevance for using Twitter with groups and/or with the goal of building community. These are Twemes and Twibes. First, Twemes (short for Twitter memes, see the Wikipedia page on memes) are a development that allows users to tag their tweets on a particular topic in order to aggregate them online. This is as simple as using the # sign before the topic. For example, students using Twitter in a college level ESL class who were attending a lecture on feminism could add #femlect to tweets about questions or comments they have. After the lecture, the students and teacher could search #femlect as a keyword to see (and respond to) their classmates tweets. Twitter can be searched this way, but older tweets can be hard to access over time. Another option is to use Tweme.com, an online site that tracks and archives all tagged Tweets.

Figure 4. Twemes.com page for a tagged discussion on #healthcare

Yet another option for classes is to create a Twibe. This application allows groups to create a Twitter home page with the option of tweeting only to the people in this group, thereby creating a more bounded, private community. There are many existing Twibes, with EdTech among the largest at 1876 members (as of 7/23/09).

Student Age and Language Level

Twitter is not really about being private, however. The fact that it can connect English learners with a vast live public of native language users is in my opinion, what makes it a valuable tool for learning. Therefore, it is probably more appropriate to use it publicly and with adult students. (For K-12 educational purposes, Edmodo.com is a web 2.0 microblogging platform designed specifically for secondary education, which can be used privately among students in a class or in a restricted network of users).

Students may need support in setting up Twitter accounts, even those who are tech savvy and experienced with text messaging. Although at an estimated 92% usage rate (Pempek, Yermolayeva & Calvert, 2009) college students are nearly universal users of Facebook, they are not currently using Twitter as widely (Mansfield, 2009; Joly, 2009). About 19% of 18-24 year olds were using Twitter as of February 2009 according to the PEW Internet Project Memo on Twitter (Lenhart & Fox, 2009). In my recent experience with international students trying out Twitter in the spring of 2009, there were many students who had not heard of it and no students who were using it before it was introduced as a class tool. The students in this group were intermediate English users, but Twitter has something to offer beginners as well. Specifically, Twitter can provide a way for a beginning level student to participate in an English speaking community in a peripheral, but legitimate way. This brings me to the pedagogical section of this article where I will suggest how Twitter can be a valuable tool for ESL teachers and learners based on a situated and socio-cultural view of language learning.

Affordances of Twitter for Education and Language Learning

Twitter’s purpose is user-dependent. It has been co-opted as a tool for professional development, advertising, location tracking, political activism, research, and even artistic creation. At its core though, it is a social networking tool that enables a variety of social and cultural practices. Twitter can become an important way for an online community to connect, share information, and even produce something. The potential of Twitter for language learning is not about comprehensible input and output; it is about engaging learners in social practices and participation in communities of English language users. I have empirical evidence of Twitter’s value as a tool for connecting a classroom of learners, but I am more intrigued by its potential to provide English learners with access to the larger English speaking society and to other communities of practice in which they wish to participate.

Building Classroom Community

My experimental use of Twitter with a class of new ESL students was inspired by professor David Parry’s blog, where he detailed his success in using Twitter to build classroom community with students in his Communications course. Parry had several other creative suggestions for Twitter use in academia (see References). My idea was to have new students and the teacher in an intensive English program class use Twitter to get to know each other by tweeting about what they were doing outside of class during the initial weeks of the course. Building a classroom community is important since students may participate more actively if they feel comfortable with others and if there is a sense of common purpose. It was relatively easy for students to set up and learn how to use Twitter. The assignment was simply to follow other students in the class (and teacher) and post three tweets per week.

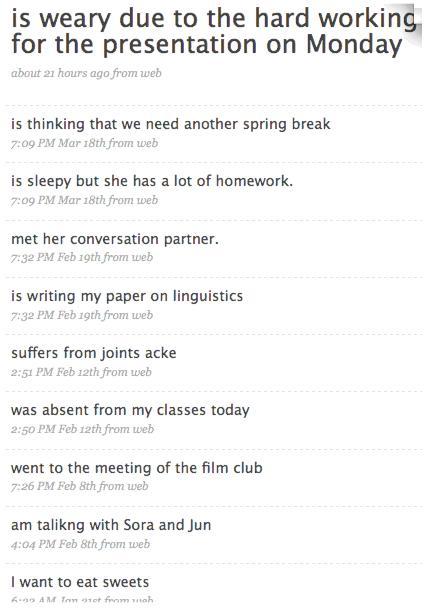

The outcome was quite positive. Not only did students follow each other, they began to have conversational exchanges. Their tweets demonstrated concern and support for each other. It was important to become aware of some of the issues that students raised: loneliness, boredom, homesickness, and confusion. This ambient awareness of the students as they adjusted to a new culture resonated with what journalist Clive Thompson described as Twitter’s creation of “a sixth social sense” (Thompson, 2007). Twitter allowed students to connect in an informal social way and bring up topics they might not have raised in the classroom. A survey of participants revealed that the majority felt Twitter had helped them get to know each other better and become more comfortable participating in the classroom. Though the focus was not on language development, most students felt that using Twitter helped them practice and learn English. It was interesting to see from looking at individual student’s home pages that Twitter posts became longer and sometimes more complex over the course of the 5-week experiment.

Figure 5. A student’s Tweets over 5-week period (Newest tweets are at the top).

Further details of this experiment can be found on the webpage created for my presentation at TESOL 2009 titled “Is Twitter a Tweet for Community Building?”

Connecting With Communities Beyond the Classroom

In making some specific recommendations for Twitter use for ESL, I adopt a situated learning perspective and associate second language learning with the concept of Legitimate Peripheral Participation developed by Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger (1991). Situated learning, in contrast to an information processing view, is a context-based theory of learning centering on the emergence of meaning, understanding and identity through the dynamics of social interaction. Legitimate Peripheral Participation (Lave & Wenger, 1991) describes social practices whereby a newcomer has access to membership in a community through participation, initially perhaps at the periphery, but potentially reaching full participation. For the English as a second language learner, the community of English users may be a community of practice in which participation is a general goal, and communities in which the learner needs or intends to participate, nested within or interacting with this larger community, may be communities of practice on other learning trajectories.

Socio-cultural theories of language learning also emphasize the processes of negotiating meaning and identity. In taking these two theoretical perspectives together, designing for learning involves supporting the learner’s goals of becoming who they wish to become. The role of the teacher is to facilitate the learning process, not by delivering information in a simplified abstracted form, but by engaging learners in ways of attending and acting that will provide them with opportunities for increased participation in communities of practice.

Twitter provides several affordances for extending language practice beyond the boundaries and community of the classroom. In addition to some of my own ideas, I will recommend several Twitter activities from an online educator resource called “Twenty-five Interesting Ways to Use Twitter in the Classroom.” Many of these activities are designed for younger learners and therefore suggest that the teacher use his or her own Twitter network; however, for adult learners, creation of individual networks is highly desirable.

Supporting Meaningful, Engaged Language Learning in Authentic Contexts

1) Conversation and interaction in communities of English users

Twitter allows users to direct messages using the @user name feature. This feature allows the English learner to interact in the target language and negotiate meaning through conversation. Conversation is the locus of meaning making and the main activity in which an ESL learner develops their English user identity. Twitter wasn’t created to support dialog, but there is evidence that it is increasingly being used conversationally (Honeycutt & Herring, 2009) and there are a growing number of tools for capturing these interactions.

Although English learners may hesitate to engage in direct messaging, there is evidence that lurking, reading and observing the online interactions of others, can be a beneficial part of learning and a phase that leads not only to more visible participation but also to greater satisfaction with online discussion as a source of learning (Dennen, 2008). Lurking can be a form of legitimate peripheral participation. Conversations in Twitter can readily be observed within Twitter groups or Twibes, where members are focused on specific topics or questions. Following hash tagged (#topic) conversations is also easy to do and often an interesting way to see the diversity of opinions on culturally trending topics. One of the simplest initial activities with Twitter is to have students choose someone to follow and after a week or so, report on their findings–what they have been able to learn or what they infer about this person based on their tweets. There may be not be any conversational exchange, but this can still be an initial form of participation in the Twitter community.

From a socio-cultural perspective, participating in online discussion has several affordances for language learning that are lacking in face to face contexts: freedom from the turn-taking rules that exist for face-to-face conversation, more equal opportunity to have the attention of others or to have “the floor”, and opportunities to take on different roles than would be likely in other kinds of interactions (Hanh & Kellogg, 2005). Furthermore, Hanh and Kellogg (2005) proposed that the roles learners do take on affect their opportunities for future participation, and this impacts their identity and learning. This suggests a benefit to raising learner awareness of the dynamic interplay between participation, identity and learning. Through archiving and reflecting on Twitter conversations students can be tuned to noticing how their language and manner of participation connect with their learning opportunities.

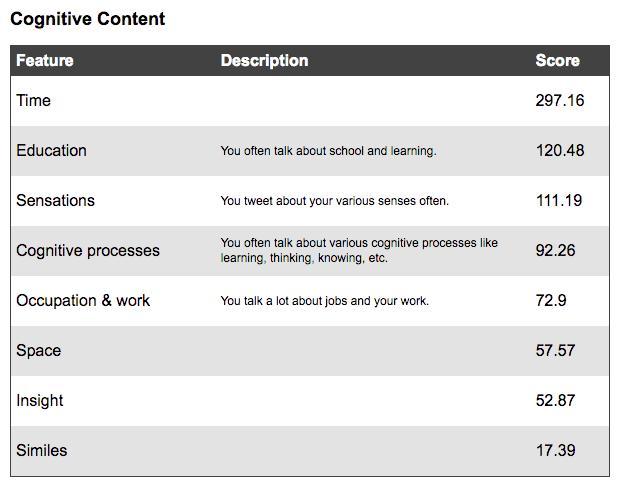

A fun way for students to consider and become more aware of their English user identity after they have been using Twitter for some time, is to do a quick activity with TweetPsych. Here is a part of my psychological profile; scores show number of tweets matching each feature that exceed a baseline score.

Figure 6. My psychological profile based on Twitter Tweets from TweetPsych

Twitter can engage learners in conversation with native English speakers through:

- Creative storytelling (see #4 Tweetstory in “Twenty-five Interesting Ways to Use Twitter in the Classroom” by Barrette, Belshaw, & et al.)

- Polling and comparing opinions within and outside of the class (see #9 TwitterPoll)

- Creative role play of fictional/historical characters who can be followed and tweeted (see #21 Twalteregos)

2) Collaboration and construction of knowledge

Twitter can be used as a tool to complement collaborative practices such as problem or project based learning, jigsaw learning, or reciprocal teaching that can be employed in content-based language activities and courses. Students can easily share information and use each other (and others in the extended online community) resourcefully in their search for information, opinions, or help. This interchange can be captured and used as a tool for reflection. Twitter can be employed as a backchannel during listening activities (lectures, movies, newscasts) to allow students to share comments, questions and notes, providing the teacher with an opportunity for just in time teaching or scaffolding.

Some other ideas for collaborative uses of Twitter:

- Engage in a research project with students in another location by mutually following each other’s tweets on the topic (#11 Come Together)

- Use Google Earth to find Twitter users based on a single piece of location information (#13 Geo Tweets)

- Survey Twitter users to get a global perspective on some topic of current local or national interest (#14 Global Assembly)

3) Immediacy, mobility, asynchronous dialoging and archiving

The real-time communication and search features supported by Twitter and associated applications afford on-demand access to an online network, and up-to-the-minute information and conversation on topics of popular interest. This access to the “super fresh web” (Johnson, 2009) can provide a unique resource for language help that is more communicative and contextualized than a dictionary or translator. There is evidence supporting the use of Twitter to increase social presence and “free flowing interaction” in online courses through its ease of access and use compared to discussion boards within Course Management Systems (Dunlap & Lowenthal, 2009).

Since Twitter can be used on mobile devices, it can provide a tool to capture field-based learning and capitalize on the advantages of asynchronous learning. In a pilot study by educators at the Open University in the UK, mobile blogging was employed with the goal of encouraging students of Spanish who were traveling in Spain to be more aware (and perceptive) in the new culture. Students blogged to share experiences with classmates who did not join the trip. Blogging was used to engage students in dialogue in order to make sense (or meaning) out of the foreign culture and provide a means to extend learning across timeframes to allow for reflection (Comas-Quinn, Mardomingo & Valentine, 2009). The authors noted the benefits of mobile technology for informal “accidental” learning, and learning in and across contexts.

Archiving of tweets, whether individually or in a group framework, allows space for learners to extend a discussion or reflect on their learning without the constraints of time or location, facilitating development of metacognitive practices. The visual record of interaction can facilitate the negotiation of meaning (Hanh & Kellogg, 2005).

These activities take advantage of Twitter’s immediacy and mobility:

- Use Twitter to ask for synonyms, antonyms, etc. and assemble the results (#10 WordMorph)

- Tweet during a trip to provide instant communication and a record of events, photos, even videos (try Twitcam.com) (#23 Track with Twitter)

4) Authentic language use and academic practices

Following a cognitive apprenticeship approach, an instructor can guide the learner’s attention and intention for Twitter use by modeling how she uses the tool, for example to participate in a professional community of practice by selectively following others, scanning tweets, and interacting in a way that adds value to the group. Likewise, a teacher or other knowledgeable user can model how they write succinctly or for a specific audience by describing their thoughts and actions as they compose a tweet. A teacher can also model how to search a term to see how it is used in the various contexts of native speaker tweets. In raising the learner’s awareness to patterns in authentic language use, the teacher can draw the learner’s attention to Twitter’s affordance of a rich “semiotic budget” (van Lier, 2004), an easily accessible warehouse of English–in its living, breathing state.

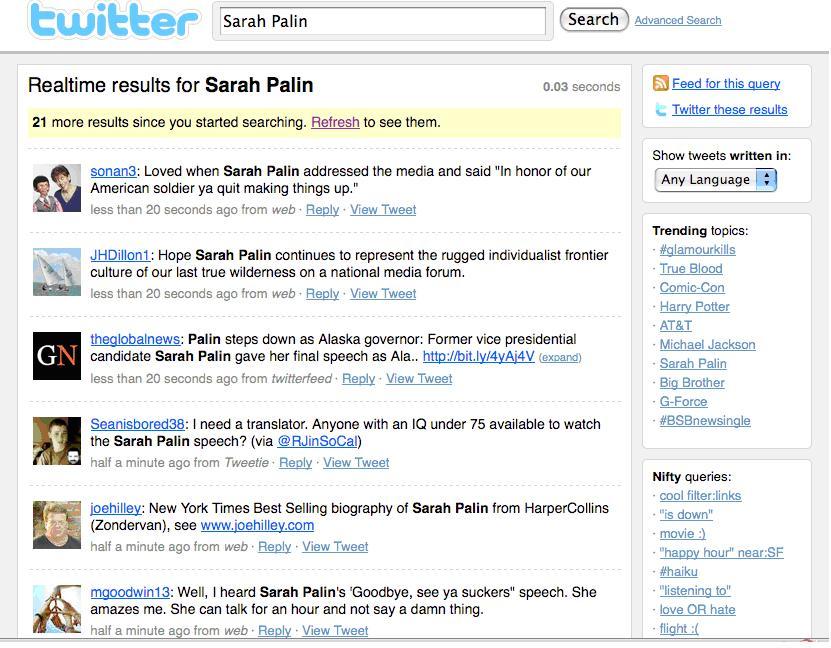

There are several online tools for key word searching of Twitter. Summize.com works as a search engine, which could be useful for both word searching and research, and Twitterfall.com provides a real-time view of tweets as they are made on a given topic.

Figure 7. Keyword search result for “Sarah Palin” on Summize.com 7/26/09

The Time cover story on Twitter predicts a future in which our online social networks will be our primary information sources and more importantly, will provide our best access to the information that most interests us (Johnson, 2009). Participation in online communities is thus an important social practice for our students to develop as one of the new literacies. It can serve the dual purpose of facilitating language learning when second language learners connect with target language users who share similar values, interests, and goals.

The following are recommended activities that entail authentic research practices and extend learning beyond the classroom community:

- Survey the network to collect data (#1 Gather real-world data)

- Search a topic using Twitterfall and find our where in the world the tweets are coming from (#2 Monitor, Geo-tag the “Buzzwords”)

- Collect resources by posting links to online sites (#22 Scavenger Hunt)

- Use Twitter to post and archive research observations and findings (#25 Research Diary)

Summary

For adult ESL learners with a computer or a mobile phone and the intention of using English in contexts beyond the classroom, Twitter can indeed be a powerful tool. The affordances are numerous: access to native English speakers, opportunities to participate in online communities, searchable authentic language in context, and the capability of grouping and archiving tweets. Twitter may not be for everyone however. Although it is easy to use, its benefits may not be immediately apparent to a new user. While it has over three million users, it may initially, in the words of one of my student, “feel cold.” The lack of response to many tweets may put off learners who are seeking a good immediate conversation. There will undoubtedly continue to be technical issues, though these seem to have subsided since June of 2008 when Vance Stevens predicted the possible abandonment of Twitter due to frequent server overloading (Stevens, 2008).

Dunlap and Lowenthal (2009) offer some useful guidelines for Twitter use with students based on their experiences in several online courses. They first stress the importance of making the purpose of using Twitter transparent. This can be accomplished by modeling some of the ways Twitter is used by regular users, both for fun and for more serious or professional purposes. Another suggestion is to state clearly the level of Twitter participation expected and how this relates to projects and the student’s final grade or evaluation. Finally, teachers need to demonstrate their own commitment to Twitter by using it, not only during the course, but afterward, in order to encourage students to continue to use it for their own ongoing learning and personal network development.

Twitter and other technology tools will only be adopted by learners when they are perceived as moving them closer to some goal. I believe that learning is about the education of attention and intention (Young, 2004). As language teachers, we should create learning opportunities that raise awareness of language learning as a social practice that emerges from active and meaningful participation in communities. We can promote adoption of the goal of increasing participation by designing for learning in authentic situations that allow for autonomy and on-demand learning. We should increasingly require of learners not linguistic output based on some input received, but improvised action based on attunement to the language and sociocultural practices of the community. With access to interactive experiences and environments within communities of practice, the learner can become more attuned and feel more legitimacy as a user of the language.

References

Comas-Quinn, A., Mardomingo, R., & Valentine, C. (2009). Mobile blogs in language learning: Making the most of informal and situated learning opportunities. ReCALL, 21, 96-112.

Dennen, V. P. (2008). Pedagogical lurking: Student engagement in non-posting discussion behavior. Computers in Human Behavior, 24 (4), 1624-1633.

Dunlap, J., & Lowenthal, P. (2009). Tweeting the night away: Using Twitter to enhance social presence. Journal of Information Systems Education, 20 (2).

Grosseck, G., & Holotescu, C. (2008). Can we use twitter for educational activities? Paper presented at the 4th International Scientific Conference eLearning and Software for Education, April 17-18, 2008. Bucharest, Romania. Retrieved September 3, 2009 from http://adl.unap.ro/else/contentpapers.php

Hanh, T. N., & Kellogg, G. (2005). Emergent identities in on-line discussions for second language learning. Canadian Modern Language Review, 62 (1), 111-136.

Honeycutt, C., & Herring, S.C. (2009). Beyond microblogging: Conversation and collaboration via Twitter. Paper presented at The 42nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, January 5-8, 2009. Waikoloa, Hawaii. Retrieved September 3, 2009 from http://www2.computer.org/portal/web/csdl/proceedings/h#5/

Johnson, S. (2009, June 5). How twitter will change the way we live. Time. Retrieved September 3, 2009 from http://www.time.com/time/business/article/0,8599,1902604,00.html

Joly, K. (2009). Should you twitter? University Business, 12 (1), 39-40.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. C. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Lenhart, A., & Fox, S. (2009). PEW Internet Project Data Memo, Twitter and status updating. Retrieved July 28, 2009 from http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2009/Adults-and-Social-Network-Websites.aspx

Mansfield, H. (2009). 10 twitter tips for higher education. University Business, 12 (5), 27-28.

Newgarden, K. (2003). Is Twitter a tweet for community building? Retrieved September 1, 2009, from http://homepage.mac.com/knewgarden/KNEPortfolio/documents/TwitterPres.html

Pantanacce, L. (2009). TwitDir.com. Retrieved September 1, 2009 from http://twitdir.com/search_lite.php

Parry, D. AcademicHack blog 1/3/08 entry: Twitter for Academia. Retrieved July 27, 2009, from http://academhack.outsidethetext.com/home/2008/twitter-for-academia/

Pempek, T. A., Yermolayeva, Y. A., & Calvert, S. L. (2009). College students’ social networking experiences on Facebook. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30 (3), 227-238.

Pfeifle, M. (July 6, 2009). A nobel prize for twitter? The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved September 3, 2009 from http://www.csmonitor.com/2009/0706/p09s02-coop.html

Stevens, V. (2008). Trial by twitter: The rise and slide of the year’s most viral microblogging platform. Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language, 12 (1). Retrieved September 3, 2009 from http://tesl-ej.org/ej45/int.html

Thompson, C. (June 26, 2007). Clive Thompson on how Twitter creates a social sixth sense [Electronic version]. Wired Magazine. Retrieved July 29, 2009 from http://www.wired.com/techbiz/media/magazine/15-07/st_thompson

Twenty-five interesting ways to use Twitter in the classroom. (n.d.). Retrieved September 3, 2009 from http://docs.google.com/present/view?id=dhn2vcv5_118cfb8msf8

van Lier, L. (2004). The Ecology and semiotics of language learning. Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Young, M.F. (2004). An ecological psychology of instructional design: Learning and thinking by perceiving-acting systems. In D. H. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of Research for Educational Communications and Technology. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

About the Reviewer

Kristi Newgarden is an ESL teacher and director of the University of Connecticut American English Language Institute (UCAELI). She is currently a doctoral student in Educational Technology at the same university. Her interests are in computer assisted language learning and language learning in virtual worlds. She is interested in understanding how technologies can facilitate second language learner participation in communities of practice. Her professional information can be found at: http://web.me.com/knewgarden/KNewgarden/Welcome.html and she can be followed on Twitter at: kuri888

| © Copyright rests with authors. Please cite TESL-EJ appropriately. |