June 2010—Volume 14, Number 1

Toward a Pedagogy of Intercultural Understanding in Teaching English for Academic Purposes

Anne Jund

University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa

<annec![]() hawaii.edu>

hawaii.edu>

Abstract

This paper takes a social constructivist position of culture, identity, and classroom discourse in exploring the “culture talk” of international students in a university English for academic purposes (EAP) course. The analysis focuses on the interactional work being accomplished by the students as they participate in a classroom task about traditional clothing. Results show how participants used cultural affiliations and disaffiliations systematically in their talk to establish competing discourses and to make available multiple identities, which were then taken up and transformed by co-group members. Implications of this study relate communicative practices that take place in university EAP courses and the possibilities for teachers to move beyond a compare-contrast approach to teaching and learning culture toward a pedagogy of intercultural understanding.

Introduction

People from societies around the world are crossing national, linguistic, and cultural borders more than ever before. Many are seeking the credentials that will allow them to participate in an ever globalizing world in which the English language has arguably become a key factor for success. An examination of schools and universities reveals that global forces are impacting current education practices, and that the intersections of globalization, education, and English can be identified in a range of formal learning contexts. In the United States, the enrollment of international students is on the rise. For these individuals, English language proficiency is often a prerequisite that determines whether or not they will be accepted into undergraduate and graduate degree programs. Before gaining access to the education that they seek, “non-native” speakers are often required to jump through various English-language hoops, such as that of satisfactory achievement on the TOEFL [1] test or completion of required English for academic purposes (EAP) courses. EAP differs from other English as a second language (ESL) and English as a foreign language (EFL) learning contexts in that the majority of EAP students are preparing to enter higher education as full-time, degree-seeking students. Their needs, therefore, include more than English language proficiency. They also need to know the “rules of the game” in order to successfully navigate the college experience in an unfamiliar country.

In an attempt to prepare students for mainstream college courses, many models of academic English education present linguistic skills alongside lessons about national, ethnic, or academic culture. Culture, whether taught as part of the explicit or implicit curriculum of EAP courses, can encompass a wide range of themes and topics. Some educational models emphasize teaching and learning information about cultural objects and products (often “high culture,” such as art and literature), ways of life, and attitudes of native English speakers with the aim of acculturating international students to the norms and behaviors of mainstream American students. However, other frameworks have been proposed that take a more intercultural stance. For instance, Singh and Doherty (2004) have observed how EAP classrooms in institutions of higher education act as “global university contact zones,” which are “spaces of intercultural import-export and of transculturation” (p. 4). The concept of a global university contact zone redefines the learning and teaching of culture from a one-way transmission of knowledge to a multidirectional flow of information and treats students’ first culture (C1) experiences as resources for learning what they need in order to be successful in the target culture (C2). Global university contact zones are sites where distinct cultures converge and merge, as international students negotiate various aspects of their own culture, the target culture, and each others’ cultures.

The motivation for this study comes from my experiences in the classroom and the questions that I have about the learning and teaching of culture with groups of international students. My research questions relate to how international students negotiate the representations of their distinct cultures and how they deal with the multiple, contradictory aspects of culture in a global educational setting. To explore my questions, I collected interactional data from my own students who were enrolled in a language program at a university in the United States. I focus my analysis on the interactional work being accomplished by the students as they communicate with one another during a group task. The findings reveal interesting insights into how the students arranged and rearranged cultural objects, activities, and actions into categories while discussing the topic of traditional clothing in various cultures. Yet, my analysis goes beyond the level of talk by considering the extra-discursive aspects of discourse as well, so as to provide insights into how the speakers constructed multiple meanings of culture, cultural difference, and cultural identity. Results show how participants used cultural affiliations and disaffiliations systematically in their talk to establish competing discourses and to make available multiple identities, which were then taken up and transformed by co-group members. Following my analysis, I discuss certain concepts that have emerged from the data; specifically, the concepts of contrastive cultural analysis and conflicting discourses as possibilities for intercultural learning. Pedagogical and curricular suggestions are provided that may aid teachers in creating spaces for international students to achieve cross-cultural understanding and to develop intercultural relationships between members of the global community. I begin by presenting my conceptual framework for this study, which adopts a discursive position of culture, identity, and classroom talk.

Conceptual Framework

Locating Culture in Classroom Talk

In exploring the “culture talk” of my students, I draw from social constructivist understandings of classroom discourse. In this view, EAP classes are more than just places where people from different countries come together to learn English. More accurately, they are intercultural discourse communities in which members work together to establish intercultural relationships between people and things. From a social constructivist perspective, people use language to create social realities and, thus, culture (along with gender, race, class, power, etc.) is conceived of as a social construct, the product of discursive practices, rather than fixed, static phenomena. Within classroom contexts, students engage in a variety of communicative tasks, many of which ask them to draw on understandings from their own cultural, linguistic, and ethnic backgrounds. In this way, culture and cultural difference are “talked into being” as speakers communicate stories and attempt to collaboratively make sense of their experiences. The following excerpt from the data collected for this study helps to illustrate this point:

Excerpt 1:

| 2. | H: | Some women wear kimono in Japan?= |

| 3. | A: | =[(xxx) |

| 4. | M: | =[in their job |

| 5. | H: | Kind of costume? |

| 6. | A: | Yea as a kind of [costume. |

| 7. | M: | [Mmm::: |

| 8. | See that’s a (.) progression right. Western clothing replacing | |

| 9. | traditional clothing (.5) now. | |

| ((xx)) | ||

| 13. | M: | Because women don’t wear kimonos anymore in |

| 14. | maybe situations right so most likely | |

| 15. | (.) ninety five (.) ninety six percent | |

| 16. | of the people wear Western style clothing | |

| 17. | (2.0) |

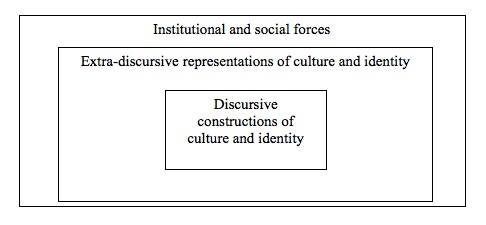

The students’ discursive construction of clothing in Japan in Excerpt (1) also reveals that multiple meanings and interpretations are possible: women wear kimono to work (line 4), women don’t wear kimono anymore (line 13), a kimono is a costume (lines 5–6), Western clothes represent progress in Japan (lines 8–9), Japanese clothing is almost completely Westernized (lines 15–16). These interpretations circulate amidst essentialist representations of culture as well, however, such as the ideas that Japanese wear kimono, Germans wear lederhosen, Americans wear cowboy hats, and so on. To negotiate a concept of culture that takes into account the multiple, changing, and conflicting meanings of culture can be a challenging task for language learners and teachers (Kubota, 2004). The process becomes further complicated by issues of cultural identity and the institutionalized nature of the talk that takes place in these intercultural discourse communities. Figure 1 illustrates how culture and cultural identity are constructed through classroom talk that takes place amidst extra-discursive representations of culture and identity, and how institutional and social forces shape these processes:

Figure 1. Constructing culture and identity in the classroom

While many teachers attribute characteristics to students based on their country of origin or assume that cultural differences are automatically present in EAP classrooms, it is important to look for evidence of how cultural identity and cultural difference may or may not emerge as a relevant construct. For this study, considering situated examples of language use and linguistic detail was an essential starting point for investigating the social realm of discourse and identity formation Blending theoretical perspectives of identity provided the tools for such analysis.

From Constructivist to Poststructuralist Identity Theory

Fundamental to this study is the notion that, along with culture and cultural difference, people use language to create an identity, or sense of self, in the world. Identity, however, is more than one’s sense of self. More accurately, it is “who we are to each other” (Benwell & Stokoe, 2006, p. 4). At the level of talk, speakers work together to produce a sense of self and a relationship to each other in the larger social world. In this sense, identity is co-constructed by participants as they interact. However, poststructuralist theories of discourse and identity can offer analysts further insights into the social realm of discourse and identity construction with which constructivist approaches are generally not concerned. Researchers who align with poststructuralist ideas are interested in how identities emerge in different ways depending on constellations of discourses. These discourses are all understood to be acting upon speakers, and speakers can act with agency to resist certain discourses, to accept others, or to transform them. Therefore, in interacting with these discourses, a person’s identity is constantly shifting, changing, and transforming. As noted in Excerpt (1), a poststructuralist view further reflects that multiple conflicting identities (or stories, historical accounts, cultural norms, ideologies) are always at play (Phillips & Jørgensen, 2001). Thus, in EAP classrooms, students and teachers with distinct historical trajectories, ethnic backgrounds, and linguistic repertoires are constantly working to “fix” meaning to make sense of the world.

Using the data in this study, drawn from various classroom interactions, I show that the nature of identity is fluid in that sometimes the cultural difference is highlighted and accepted by participants; while, in other cases, it is rejected by participants who are positioned into certain cultural identities by their classmates. The data also show how the participants encounter and deal with multiple and contradictory versions of commonsense, truth, and reality as they communicate stories of their lived experiences, negotiate representations of culture and cultural difference, and attempt to construct a shared vision of the world around them. Hence, I take an integrated stance toward examining the cultures, identities, and classroom discursive practices of my students.

Method of Analysis

This study uses discursive psychology to analyze interactional data, as established by Wetherell (1998). She considers discursive psychology (DP) as an approach to theorizing psychological states, such as attitudes, emotions, memories, and identity, and takes discursive practices as its object of analysis. DP can be used to study how people talk about, or construct, psychological things, how such accounts accomplish a range of social actions, and how speakers use the discourses that are available to them to create and negotiate representations of the world and the self. Wetherell’s (1998) version of DP, often referred to as critical discursive psychology, takes an eclectic, integrated stance toward discourse analysis. She departs from other critical approaches to discourse analysis (for example, Fairclough, 2001), however, by carrying out a fine-grained, micro-level analysis of interactional data using the tools of ethnomethodology and conversation analysis. Ethnomethodologists traditionally restrict their analysis to the situated discursive practices of participants (Schegloff, 1992); yet, Wetherell views such interactional sequences as embedded within some kind of historical context, recognizing that “when people talk, they do so using a lexicon or repertoire of terms which has been provided for them by history” (Edley, 2001, p. 190). She expands the analysis beyond the level of talk by examining the ways in which participants are not only producers, but also products of discourse (Laclau & Mouffe, 1985, 1987), both the masters and the slaves of language (Barthes, 1982).

Critical DP adopts poststructuralist theories of identity (Laclau & Mouffe, 1985), acknowledging that discourses designate subject positions for people to occupy. For example, in classrooms, certain subject positions such as teacher and student may be talked into being, and corresponding with these positions may be expectations of how to act, what to say, and what not to say. Critical DP researchers are interested in the ways people identify with the various subject positions made available to them through discourse. However, never is only one subject position at play; rather, several competing subject positions operate on individuals. Therefore, the subject is said to be “de-centered” in that it is “positioned by several conflicting discourses among which a conflict arises” (Philips & Jorgensen, 2001, p. 41).

Following Wetherell (1998, 2007), I aim to conduct a fine-grained analysis of interactional data to uncover how culture and identity are shown to be real by participants in an interaction. Yet, a poststructuralist analysis must go beyond the level of talk and consider the extra-discursive aspects of discourse so as to provide insights into how participants use linguistic resources circulating in the social world to construct multiple and fragmentary selves. The objective of my analysis is, therefore, to examine the discursive construction of culture, knowledge, and identity among EAP students engaged in classroom discussions by addressing the following research questions:

- How do participants go about creating, ascribing, and resisting cultural identities?

- How is knowledge of the social world co-constructed by participants engaged in classroom talk and for what interactional purposes?

- How are participants’ discursive practices related to pedagogical notions of intercultural awareness and understanding?

Data Collection, Context, and Participants

The data for this study come from audio-recordings of 12 small-group interactions, each 10 to 20 minutes long, which took place in April and May 2008 in a university EAP class that I was teaching. This was a content-based course that was developed out of expressed student interest in learning about clothing and fashion. I organized curriculum and materials for the course around themes and issues related to clothing and fashion, which served as a springboard for learning a set of academic English skills. In developing the course, I used a critical pedagogy approach to examine the roles and relationships between history, industry, and the media with regard to the choices people make about what they wear. Students in the course were required to read texts, watch videos and write about topics such as school uniforms, underweight fashion models, the use of animal fur in fashion, consumerism and shopping addiction, environmentally-conscious fashion, and more. The participants in this study were intermediate and advanced English language learners from diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Seeking to understand more about the transculturation processes that international students underwent as they engaged with the cultural content of the course, I recorded tasks, activities, and discussions as they occurred in this classroom and transcribed the interactions following conventions adapted from Atkinson and Heritage (1984) (see appendix).

Results

In this section, I present one excerpt of classroom discourse that reveals how participants discursively arrange and rearrange cultural objects and practices into collections and how such collections acquire different meanings depending on their situated uses. The data also show how competing discourses emerge in talk to create multiple subject positions which are then taken up and transformed by members.

One of my goals in developing this course was to provide spaces for students to act as cultural experts by introducing content that would encourage them to draw on their existing first culture knowledge. As a way for them to inference schemata from their home cultures, I adapted materials from a textbook chapter on the topic of traditional clothing (Solórzano & Schmidt, 2004). The first part of the task asked students to look at two photographs of a woman and to compare and contrast the different styles of dress she was wearing in the photographs; in one photograph the woman is wearing a sari and in the other she is wearing a business suit. Next, the students listened to a simulated radio interview with the woman, who spoke about the cultural norms of wearing saris and sarongs versus Western clothing in Sri Lanka. After listening to the audio-recording, I divided the class into small groups and instructed them to discuss the following quotations and reflection questions based on the interview:

- “People who live in the countryside still wear sarongs. But in the city, men wear pants and shirts.”

- Is the same thing happening in your culture? Is Western clothing replacing traditional clothing?

- Should people be encouraged to wear traditional clothing rather than Western dress? Why or why not?

- “When you’re older, you can see the value in traditional clothing more. When you’re younger, you’re most interested in being in style.”

- Do you agree with the statement?

- Do you like to wear traditional clothing from your culture? Why or why not?

(Solórzano & Schmidt, 2004, p. 132)

In one of the small groups, Moto, Linda, Hee Jung, and Akako began the interaction by discussing traditional clothes in Japan and then moved to talking about traditional clothes in Korea. In Excerpt (2), the focus of the discussion has now turned to the topic of traditional clothing in Taiwan:

Excerpt 2:

| 30. | M: | How is it in Taiwan? | ||||||

| 31. | L: | Taiwan (.5) I think like maybe speaker they wear the kind of traditional | ||||||

| 32. | clothes in the (xxx) [maybe countryside]= | |||||||

| 33. | H: | [ahhhh:] | ||||||

| 34. | M: | [ohhh:] | ||||||

| 35. | L: | =not in the city maybe countryside | ||||||

| 36. | H: | What is traditional clothing in Taiwan? | ||||||

| 37. | A: | She knows Chinese | ||||||

| 38. | H: | >Hmm?<= | ||||||

| 39. | L: | =It’s different. Taiwan native-speaker is different from Chi[na | ||||||

| 40. | A: | [Ahh: I thought | ||||||

| 41. | that (.5) >okay I [thought that< | |||||||

| 42. | L: | [yeah (.5) in China is chi pao ((旗袍)) right [yeah] | ||||||

| 43. | H: | [ahhhh] | ||||||

| 44. | M: | Chi po? | ||||||

| 45. | L: | Chi pao is like uh (1.0) I don’t know how to | ||||||

| 46. | (.5) | |||||||

| 47. | M: | Is it like one of those= | ||||||

| 48. | L: | =very neat and tight you know [the (xxx)] >yea yea yea yea< | ||||||

| 49. | M: | [(xxx)] | ||||||

| 50. | M: | What do you call it? Sh[e pao? | ||||||

| 51. | A: | [Chi pao= | ||||||

| 52. | M: | =Chi pao= | ||||||

| 53. | A: | =Chi pao | ||||||

| 54. | M: | That’s what it is chi:::: pao (.) man I like chi pao | ||||||

| 55. | L: | ((laughs)) | ||||||

| 56. | L: | ((addressing classmate from other group)) NO:: IT’S CHINESE | ||||||

| 57. | M: | Chi pao | ||||||

| 58. | H: | Taiwan is Chinese? | ||||||

| 59. | L: | Kind of (.) I don’t know because it’s sensitive topic= | ||||||

| 60. | H: | [=Ahhhh:] | ||||||

| 61. | A: | [How] do you write chi pao? | ||||||

| 62. | L: | Chi pao is China I think | ||||||

| 63. | M: | Okay ((begins reading from handout)) | ||||||

In line 31, Linda provides a response to Moto’s question about Taiwan. Linda displays knowledge of Taiwanese people living in the country, who may wear traditional styles of clothing, versus people living in the city, who do not. In line 36, Hee Jung orients to Linda’s presumed cultural knowledge of Taiwan, yet Akako takes the next turn and creates a subject position for Linda as someone who knows Chinese. Linda resists this subject position and, in line 39, attempts to create a disassociation between Taiwan native speaker and China. However, in her next turn, Linda self-orients to an identity of cultural expert of Chinese traditional clothing, when she displays lexical knowledge of a garment traditionally worn in China, chi pao. This is an example of how cultural expertise is often claimed by “non-members” of a culture (Zimmerman, 2007). Linda displays knowledge of Chinese culture yet distinguishes between China and Taiwan. Therefore, her subject position of Chinese or expert on Chinese clothing is different from that of her co-participants.

In the series of talk that follows, Linda’s identity as an expert knower of the Chinese cultural object chi pao is co-constructed by the other participants, who directly ask her to clarify the pronunciation and physical characteristics of chi pao. In line 56, Linda responds to a question from a classmate belonging to a different small group. Although the classmate’s talk is inaudible, based on Linda’s response, chi pao was likely treated as a Taiwanese cultural object. Linda’s reply is notably louder, possibly indicating some degree of annoyance or frustration. By saying, “No, it’s Chinese,” Linda reorients chi pao from a Taiwanese to a Chinese cultural object. In line 58, Hee Jung asks Linda if “Taiwan is Chinese.” Linda hedges her response with “I don’t know” before alluding to the controversial nature of Hee Jung’s question. Directly following, Akako orients to Linda’s previously established identity as having expert knowledge of chi pao when he asks her how to spell the word. In response, Linda downgrades her knower status by saying “chi pao is China, I think” and not providing an answer to his question.

In this segment of talk, cultural identity is interestingly constructed and reconstructed, as evidenced by Linda’s shifting subject positions. Initially, the subject position of someone knowledgeable of Chinese traditional clothing emerges in the talk for Linda after she is positioned this way by the other group members. As the interaction unfolds, Linda is repeatedly positioned this way by two co-group members and one classmate from a different group. Eventually, Linda establishes a contrasting or counter-subject position, that of someone uninformed about Chinese traditional clothing. Within the local context of its production, Linda’s shifting subject position functions to establish an identity as someone without the knowledge of the garment chi pao. However, the broader social implication is that this shift diverts the topic of the conversation away from talking about China and, thus, lends itself well to Linda distancing herself personally from the issue of China-Taiwan political relations.

Not only is Linda’s social construction of the self of interest, but also significant are the constraints on the range of subject positions made available to her by the other participants in the interaction. Linda’s co-group members produced coherent, consistent accounts of Taiwan’s relationship to mainland China, namely, that Taiwan and China are the same country and/or culture. They brought into play their shared, collective knowledge, which ultimately limited the available subject positions for Linda to occupy. Therefore, the objective of the task and materials was not fulfilled for Linda, as she was never given a chance to act as a cultural expert on traditional clothing in Taiwan.

Discussion and Conclusions

The prominent themes that emerged from the data relate to classroom communicative practices that take place with diverse student populations. The potentially problematic nature of communication among speakers from different cultures has led to various theories of learning, teaching, and assessing cross-cultural communicative competence in second language education (e.g., Alptekin, 2002; Ito, 2002; Leung, 2005). Theories tend to emphasize differences between cultures, such as in the above example that, “People who live in the countryside still wear sarongs. But in the city, men wear pants and shirts” (Solórzano & Schmidt, 2004, p. 132). Despite good intentions, contrastive approaches may embody reductionist ideas of cultural difference that oversimplify or stereotype groups, as was the case for Linda, whose classmates viewed her as Chinese. Byram (2008) has noted how this cultural difference stance reflects a rather 20th century approach to language education that tends to reinforce boundaries and borders rather than engage with the very global and transnational aspects of students’ 21st century classroom experiences today.

Consequently, teachers can design lessons and materials that move beyond a compare-contrast approach to culture. For example, after recognizing that much of the dialog about clothing and fashion taking place with my students was following a compare-contrast model, I began searching for alternative resources and came across the work of Barthes (1967, 2006). He was a semiologist whose ideas contributed extensively to contemporary theories of fashion, which I then incorporated into the class as a way of introducing my students to his concept of fashion as a system of signs and symbols that provide mental clues about a person’s individual and group identity. This led to a fascinating class discussion about how cultural attitudes are reflected in perceptions of what is “in-fashion” and what is “out-of-style.” Thus, we were able to extend our classroom “culture talk” beyond conversations such as “Japanese wear kimono and Chinese wear chi pao.” Later, in discussing my research findings with a colleague from India, I learned that it is common for Indian women who wear sari to mix traditional fabrics with Western shapes and lengths and that the way that an Indian woman ties her sari largely depends on where she lives, her age, and her level of education. I think it would have been worthwhile to incorporate these examples into the listening task about saris in Sri Lanka as a vehicle for learning about concepts such as cultural hybridity and in-group variation and how cultural practices of wearing traditional clothing are not straightforward or generalizable, but rather complex, multifaceted, and influenced by dynamic historical, political, geographic, and generational issues.

The analysis of the data for this study has also led me to consider how competing discourses that emerge in classroom “culture talk” can be treated as valuable learning opportunities. In Excerpt (2), when Linda’s classmates imposed the subject position Chinese on her, she challenged their positioning by disaffiliating herself from chi pao. This shift from an insider to an outsider perspective of chi pao allowed her to establish a counter-subject position of Chinese as a way of resisting the prevailing understanding among the group members. In moving toward a pedagogy of intercultural understanding, teachers can help students unravel and make sense of limited cultural depictions that are present in classroom talk, such as Taiwanese is the same as Chinese. With Linda and her classmates, this could be accomplished by turning their competing discourses of chi pao into a teachable moment by shifting the focus of the lesson from talking about traditional clothing to discussing the controversial nature of Chinese-Taiwanese political relations. In this alternative scenario, Linda could have been positioned as an expert and encouraged to actively construct a more complete cultural representation of Taiwan for her classmates. Not only would this have validated Linda’s existing cultural identity, but it would also have provided the other students with an opportunity to better understand cultural relationships between members of the global community.

Note

[1] TOEFL stands for Test of English as a Foreign Language. According to the website of the Educational Testing Service (http://www.ets.gov/toefl), the company responsible for designing and administering TOEFL, more than 6,000 colleges and universities in 110 countries require TOEFL scores from international applicants.

About the Author

Anne Jund holds an MA in Second Language Studies and is currently a PhD candidate in Education at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. Her research has focused on classroom discourse, ESL/EFL curriculum development, and multicultural education. She teaches academic English to international students at a community college in Hawai‘i.

References

Alptekin, C. (2002). Toward intercultural communicative competence in ELT. ELT Journal, 56(1), 57-64.

Atkinson, J., & Heritage, J. (1984). Jefferson’s transcript notation. In J. Atkinson, & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis (pp. ix-xvi). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Barthes, R. (1967). The fashion system. CA: University of California Press.

Barthes, R. (1982). Inaugural lecture, College de France. In S. Sontag (Ed.), A Barthes reader (pp. 457-478). London: Jonathan Cape.

Barthes, R. (2006). The language of fashion. NY. Berg.

Benwell, B., & Stokoe, E. (2006). Discourse and identity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Byram, M. (2008). The intercultural speaker: Acting interculturally or being bicultural. In M. Byram (Ed.), From foreign language education to eduction for intercultrual citizenship: Essays and reflections (pp. 57-73). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Edley, N. (2001). Analyzing masculinity: Interpretive repertoires, ideological dilemmas and subject positions. In M. Wetherell, S. Taylor, & A. Yates (Eds.), Discourse as data (pp. 189-228). London: Sage.

Fairclough, N. (2001). Language and power (2nd ed.). London: Longman.

Ito, H. (2002). A new framework of culture teaching for teaching English as a global language. RELC Journal, 33, 36-57.

Kubota, R. (2004). The politics of cultural difference in second language education. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies,1(1), 21-39.

Laclau, E., & Mouffe, C. (1985). Hegemony and the socialist strategy. London: Verso.

Laclau, E., & Mouffe, C. (1987). Post-marxism without apologies. New Left Review (166), 79-106.

Leung, C. (2005). Convivial communication: Recontextualizing communicative competence. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 15, 119-144.

Phillips, L., & Jorgensen, M. (2001). Laclau and Mouffe’s discourse theory. In L. Phillips, & M. Jorgensen (Eds.), Discourse analysis as theory and method (pp. 24-59). London: Sage.

Schegloff, E. (1992). In another context. In A. Duranti, & C. Goodwin (Eds.), Rethinking context: Language as an interactive phenomenon (pp. 191-228). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Singh, P., & Doherty, C. (2004). Global cultrual flows and pedagogical dilemmas: Teaching in the global university contact zone. TESOL Quarterly, 38(1), 9-42.

Solórzano, H. S., & Schmidt, J. P. L. (2004). North Star: Listening and speaking, intermediate (2nd ed.). NY: Pearson Education.

Wetherell, M. (1998). Positioning and interpretive repertoires: Conversation analysis and post-structuralism in dialogue. Discourse and Society, 9(3), 387-412.

Wetherell, M. (2007). A step too far: Discursive psychology, linguistic ethnography and questions of identity. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 15(5), 661-681.

Zimmerman, E. (2007). Constructing Korean and Japanese interculturaliy in talk: Ethnic membership categorization among users of Japanese. Pragmatics, 17(1), 71-94.

| © Copyright rests with authors. Please cite TESL-EJ appropriately. Editor’s Note: The HTML version contains no page numbers. Please use the PDF version of this article for citations. |

Appendix (return to text)

M Moto

L Linda

H Hee Jung

A Akako

. falling intonation

, continuing intonation

? rising intonation

underline emphasis

[ overlapping talk

= latching

(xxx) inaudible

: sound stretch

>talk< fast talk

(.) micropause

TALK loud volume

((comments)) transcriber’s description of even