June 2010 – Volume 14, Number 1

Clear Speech Works

| Title | Clear Speech Works |

| Publisher | DynEd International, Inc. |

| Contact Information | http://www.dyned.com/ One Bay Plaza 1350 Bayshore Highway, Suite 850 Burlingame, CA 94010 USA |

| Type of product | Pronunciation practice software |

| Platform | PC: Windows XP/Vista/7 Mac: OS 10.3.9 + Server use: Novell Netware, Windows NT, or AppleShare with a 100Base-T connection |

| Minimum hardware requirement |

256 MB+ RAM, 625 MB of free hard disk space; CD-ROM drive for installation on individual computers; microphones and speakers or headphones |

Introduction

Listening and speaking skills are generally the primary concerns of language learners. In response to this need, many publishing companies and software developers have produced materials that aim at enhancing these skills. Although such materials are always billed as appropriate and effective learning tools by their developers, this is not always the case. Materials must be subjected to examination and evaluation from a practical perspective. The following is one practitioner’s evaluation of Clear Speech Works.

Description of the Program

Clear Speech Works is a computer program that focuses on English pronunciation. According to its developers, the program is easy to use for intermediate to advanced learners of English and offers users quite a bit of flexibility. For example, the program can be used either alone or with a teacher, and learners can choose individual lessons by themselves or from lessons deemed important for learners from a particular L1 background. Learners can also choose a male or female voice model to match their preferences. Finally, the program can be installed locally on individual computers or on a school lab network.

Currently, the program is only available for purchase by schools and universities, not by individual users. It is part of a bundle of programs that the publisher offers for K-12 schools and English education programs at universities, but can also be purchased separately. The program comes with a companion record-keeping program so that teachers can follow learners’ progress. Records can be stored and managed locally on the school’s server or on the publisher’s server.

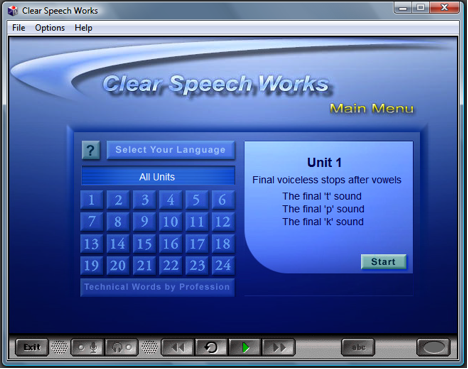

Figure 1. Clear Speech Works Main Menu

The initial screen layout (see Figure 1) displays the program’s main menu and provides the learner with buttons and toolbars necessary to navigate the program. On the left side of the screen, unit numbers, first language, and technical words buttons are displayed. On the right side, there is a box that displays information about any selection. Learners can choose to practice those units related to pronunciation difficulties associated with their first language by clicking the Select Your Language option. Learners can also choose to practice a set of technical words related to business, engineering, computers, and/or science.

The program screen also includes two tool bars at the top and at the bottom. The tool bar at the top includes three options: file, options, and help. The file menu allows user to choose to see information about the program, change the program (in case this program is used as part of a bundle of programs), or exit. The options menu allows user to access learner records, the glossary, settings/levels, or send an email. Learners can monitor their progress by clicking on the study records option. The record window displays results by unit and by subparts of each unit. The glossary option provides learners with a written explanation of how each sound is pronounced.

The tool bar at the bottom of the screen is the main bar used in practicing the content of each unit and is available on each practice screen. It includes several buttons: exit, record, listen, backward, play, repeat, forward, abc, and a timer. The exit button is used to exit the section the learner is working on. The record button is used by learners to record their voices when practicing their pronunciation. Learners can then listen to their recordings by clicking the listen button. The play button is used to listen to the voice model’s pronunciation of the words and sentences displayed; learners can listen again by clicking the repeat button. The forward and backward buttons are used to switch between screens and subsections. When the abc button is activated, the scripts of the video are displayed while it is playing. Finally, the timer shows the time spent practicing.

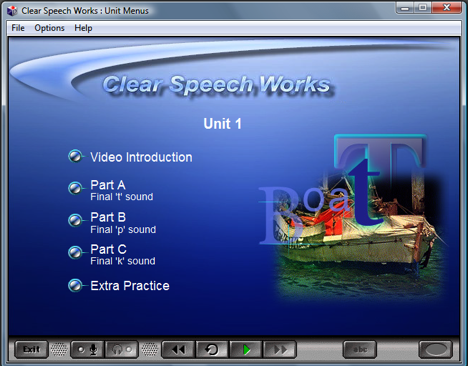

The program includes 24 units which learners select by clicking on the unit button on the program’s start screen. Each unit typically focuses on a number of consonants or vowels. Once the learner clicks on a unit, the unit main menu appears (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Unit menu

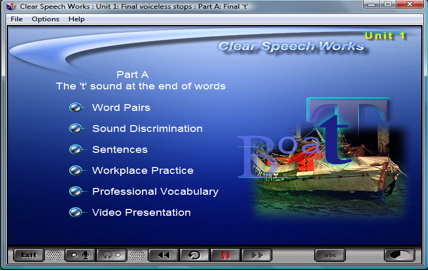

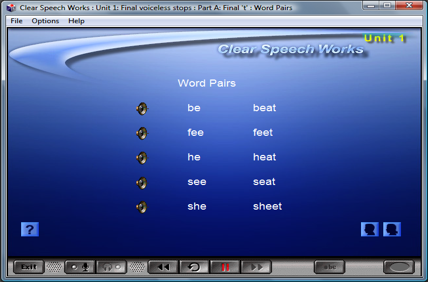

Each part of a unit includes a video introduction, two to four practice parts, and an extra practice section. The video introduction explains what type of practice learners will get in the unit, which typically includes a number of different activities (see Figure 3), such as word pairs, sound discrimination, sentences, workplace practice, professional vocabulary, and a video presentation.

Figure 3. Typical activities in each part

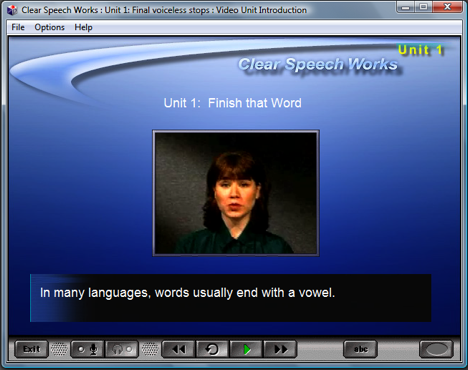

The video presentation shows and explains the manner of articulation of the unit’s target sounds (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Video presentation

Note that the activity screens (see Figure 5) have male and female icons, and learners can click one to choose their voice preference.

Figure 5. Word Pairs activity interface with voice model preference icons

In all the activities, learners listen to models and then record and listen to their own voices. No voice recognition feedback is provided.

The majority of the units provide segmental practice focusing on pronouncing discrete words, phrases, and sentences, but units 7 and 19 provide some practice with suprasegmental features such as stress, intonation, and linking.

Program Evaluation

The major strengths of Clear Speech Works are its simplicity and user interface. The interface is simple and makes the program user-friendly and easy to navigate. Consistent layouts make it easy for learners to follow the presentation of the content, and once they have tried the first lesson, they will be familiar with how to navigate the program. The option to show the scripts with the video presentations also adds to user satisfaction by providing learners with more input options.

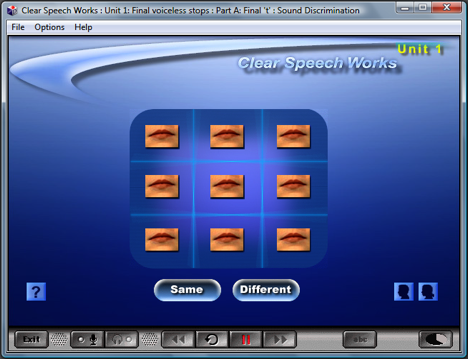

The program, moreover, does not offer a great variety of activities. In the discrimination exercise, for example, learners complete a tic-tac-toe-like game in all twenty-four units (see Figure 6). Since good design creates a positive experience for learners and can lead to more desirable outcomes (Phyo, 2003), the developers could have made an effort to include other games and types of activities. This would make the program more usable and interesting, and would enhance learners’ experience.

Figure 6. A sound discrimination activity

The program also does not offer speech recognition. While learners have the opportunity to listen to the model and then their own voices, no advanced speech recognition is integrated. While this might not be considered a shortcoming, recent ESOL pronunciation software such as Connected Speech has integrated such advanced technology. In this respect, the program might be more suitable as a classroom supplementary component where learners and teachers interact and work together, rather than as a completely self-accessed resource.

With twenty-four units and two to four parts in each unit, the first impression is that the program provides a substantial amount of content. However, after roaming around and exploring the units, the content is not as extensive as might be expected. Each part contains approximately twenty to twenty-five vocabulary words, phrases, and/or sentences. The exercises are based on sound discrimination at the first stage and then pronunciation practice drills. The integration of vocabulary in sentences and phrases gives the practice more authenticity, yet only to a limited extent. Learners do not have the chance to listen to or practice the target features in longer stretches of discourse. This might be beyond the scope of the program, but it would have been a desirable component.

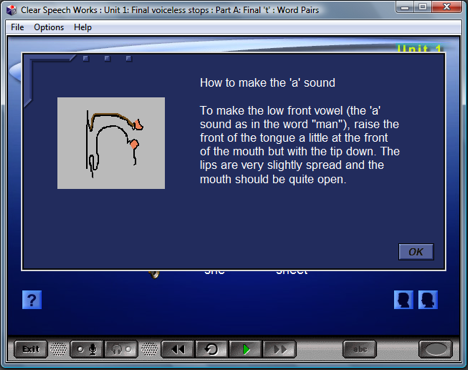

Finally, the articulation diagrams in the glossary section lack animation, which would enhance such presentations. Explanations are presented as written text, and figures are static.

Figure 7. Glossary pronunciation guidance

In sum, Clear Speech Works falls short of what one would expect of such a program nowadays, especially if we consider the three essential components of sound design: interface, information, and interaction (Liu, et al., 2008). As previously stated, the interface is straightforward and user-friendly, so the program’s design is sound in this area. However, the information and interaction aspects are less successful.

For example, although the video presentations within units give visual cues for how to articulate different sounds, it is hard to quickly access such coaching on the fly because no such video or animated support is supplied with the written explanations provided in the glossary (see Figure 7). Incorporating video or animated support here would have made it easier for learners to access specific articulation coaching and information without having to search through the units. In addition, the content of this program is somewhat limited and the type of information is mostly restricted to vocabulary, simple phrases, and sentences in isolation. The program is focused primarily on the production of individual phonemes and lacks much practice with suprasegmental features.

Finally, the interaction aspect of this software is also rather limited in that learners do not get feedback from the program on their own performance, and study reports mainly tell learners the amount of content they have finished.

In spite of these shortcomings, Clear Speech Works could definitely be used effectively as a source of supplementary exercises for a class on pronunciation.

References

Liu, M., Traphagan, T., Huh, J., Koh, Y. I., Choi, G., and McGregor, A. (2008). Designing websites for ESL learners: A usability testing study. CALICO Journal, 25, 207-240.

Phyo, A. (2003). Return on design: Smarter web design that works. Indianapolis, IN: New Riders Press.

About the Reviewer

Mansoor Al-Surmi is the CALL coordinator at the Program in Intensive English, Northern Arizona University. He is currently a doctoral student in the Applied Linguistics Program at the same university. His interests include investigating theoretical and language teaching applications in the area of discourse analysis, corpus linguistics, and computer assisted language learning.

<mansoor.alsurmi nau.edu>

nau.edu>

| © Copyright rests with authors. Please cite TESL-EJ appropriately. |