December 2009 — Volume 13, Number 3

Morphological Analysis as a Vocabulary Strategy for L1 and L2 College Preparatory Students

Tom S. Bellomo

Daytona State College

<bellomt daytonastate.edu>

daytonastate.edu>

Abstract

Students enrolled in a college preparatory reading class were categorized based on language origin. Native English speakers comprised one group and foreign students were dichotomized into Latin-based (for example, Spanish) and non Latin-based (for example, Japanese) language groups. A pretest assessment quantified existing knowledge of Latinate word parts and morphologically complex vocabulary; the identical instrument served as a posttest. Two sections on both the pretest and posttest yielded a total of four distinct mean scores that formed the primary basis for comparison.

Categorizing students within the college preparatory reading class based on language origin revealed distinct strengths and weaknesses relative to L1 status. The results of this study suggest that college preparatory students enter higher education with limited knowledge of Latinate word parts and related vocabulary. Additionally, the results evince the utility of morphological analysis as a vocabulary acquisition strategy—regardless of language origin.

Introduction

The college preparatory reading class attempts to meet the reading needs of a very diverse group of adults (Levin & Calcagno, 2008). One feature of this diversity pertains to the students’ language origin. In the state of Florida, it is not uncommon for adult English language learners (ELLs) to be in the same developmental courses as native English speakers. In preparation for college readiness, would the incorporation of a vocabulary acquisition strategy utilizing knowledge of roots and affixes be robust enough to transcend this linguistic diversity? Would such instruction prove relatively easy for native English speakers yet burdensome for ELLs? Conversely, with Latin-based vocabulary comprising roughly half of the overall English lexicon, and even more of the academic content words, would ELLs whose language is Latinate in origin perform disproportionately better? How would ELLs whose language origin is not Latin-based figure into this mix? The purpose of this experiment was to empirically investigate these questions.

Reading and Vocabulary Acquisition Strategies

Reading has been termed the linchpin to academic success. This is accentuated in higher education where students must increasingly assume the role of independent learners; additionally, much of their course content is disseminated through reading. According to Lowman (1996):

Reading remains the primary means by which educated people gain information; it is difficult to imagine a college course without reading assignments, almost always via the printed word. Even in today’s computer-rich times, when every college student must achieve a modicum of skill and comfort with computers as aids to writing or calculating, the importance of books in their many contemporary forms is undiminished. (p. 211)

Researchers have demonstrated a significant link between vocabulary knowledge and reading comprehension (Carver, 1994; Davis, 1944, 1968; Nagy & Herman, 1987; Stahl, 1982, 1990). Laufer (1997) pointed out that reading comprehension for both L1 [native English] and L2 [non-native English] students is “affected by textually relevant background knowledge and the application of general reading strategies . . . . And yet, it has been consistently demonstrated that reading comprehension is strongly related to vocabulary knowledge, more strongly than to the other components of reading” (p. 20).

Incorporating direct instruction of vocabulary into the curriculum, both for adults (Folse, 2004) and children (Beck, McKeown & Kucan, 2002; Biemiller & Boote, 2006; Nagy, Berninger & Abbott, 2003), is proliferating. Ebbers and Denton (2008) maintain, “Vocabulary instruction, and the time allocated for it, is certainly of educational significance for those who are at a linguistic disadvantage” (p. 91). Native English speakers are placed in developmental reading courses due to academic concerns indigenous to this group while the ELL students are placed therein primarily due to second language interference. When incorporating a vocabulary acquisition component with the adult in mind, instruction in strategies is perhaps the most prudent use of class time.

If it is accepted that acquisition of more vocabulary is our goal but that there are simply too many words in the language for all or most of them to be dealt with one at a time through vocabulary instruction, then what is the next logical step? Thus, one of the main classroom activities for teachers of vocabulary is the direct teaching of learning strategies related to vocabulary. (Folse, 2004, pp. 89-90)

Morphological Analysis

Morphological, or Structural, Analysis (MA) is the process of breaking down morphologically complex words into their constituent morphemes (word meaning parts). For instance, the word musician is comprised of two meaning units, the base music, and the suffix –ician; the latter conveys the meaning of an agent that is proficient in whatever is implied in the base. Hence, a musician is “one who is proficient in music.” Oftentimes, multi-syllabic words that students encounter at the collegiate level are of Classical (Greek or Latin) origin, which collectively, comprise approximately two thirds of the English lexicon (Carr, Owen, & Schaeffer, 1942). Studies have shown that as one moves along the word frequency continuum from more frequent to less frequent, the percentage of Greco-Latin words increases while the percentage of Germanic, mono-syllabic words decreases (Carr, et al., 1942; Oldfather, 1940). Words that are morphologically complex lend themselves to being decomposed into their respective meaning units; knowledge of one or more parts can facilitate as a word attack strategy or serve as a mnemonic to recall previously learned words. It is in the academic arena that students will come across an influx of content specific vocabulary throughout the curriculum. Recognizing frequent roots and affixes that transfer across the disciplines can support students as they make sense and attempt to retain the meanings of this deluge of new words. Corson (1997) noted,

Pedagogical processes of analyzing words into their stems and affixes do seem important in academic word learning. These processes help to embody certain conscious and habitual metacognitive and metalinguistic information that seems useful for word acquisition and use. Getting access to the more concrete roots of Greco-Latin academic words in this way makes the words more semantically transparent for a language user, by definition. Without this, English academic words will often remain “hard” words whose form and meaning appear alien and bizarre. So this kind of metacognitive development that improves practical knowledge about word etymology and relationships seems very relevant for both L1 and L2 development. (pp. 707-708)

Research suggesting a positive correlation between morphological knowledge and reading skill has been addressed in the context of grades K-12 (McCutchen, Green & Abbott, 2008; see also Reed, 2008 for a synthesis of the literature). A major assumption in this present research is that this same skill is requisite to reading well at the college level, especially given the preponderance of morphologically rich content words in higher education. What is lacking in the literature, though, is sufficient empirical evidence of any particular strategy productive for building vocabulary among the linguistically diverse student body found in many of today’s developmental, or remedial, reading classes.

Method

Introduction

This quasi-experimental study investigated the effect of morphological analysis as a vocabulary acquisition strategy among a heterogeneous student population enrolled in college preparatory reading classes at a community college in central Florida. Heterogeneity was viewed specifically with regard to language background. This served as the independent variable from which three levels were obtained: Latin-based (LB) foreign born students, non Latin-based (NLB) foreign born students, and Native English Speakers (NES). A pretest was administered during the first week of instruction to assess the extent of students’ prior Latinate word part and vocabulary knowledge; the same test was utilized as a posttest twelve weeks later in order to note score increases and to identify similarities and contrasts among the three levels. Though course instruction also included Greek, French, and Anglo Saxon word parts and vocabulary, the test instrument was limited to Latinate word parts and vocabulary to isolate the possible influence of background knowledge afforded the LB group.

This experiment built on a previous study (Bellomo, 1999) which sought to determine whether or not students whose first language is Latin-based have any advantage over their non Latin-based peers when learning morphologically complex vocabulary in an Intensive English program for English language learners. That initial investigation served as a pilot study from which the test instrument was subsequently enhanced and then administered to international students in an upper level reading course at an English Language Institute, and to American students who were exposed to the same methodology in a developmental reading course. Thus, the present data provide comparisons among all of the different types of students, based on language background, which could—and often do—occupy a college preparatory reading class.

Research Questions

Three principal questions framed this research. They are as follows:

- To what extent does existing knowledge of Latinate vocabulary and word parts differ among the three groups, based on language backgrounds, as indicated by a pretest? [1]

- To what extent does knowledge of Latinate vocabulary and word parts differ among the same three groups after one semester of instruction, as indicated by a posttest?

- At the end of one semester of instruction, to what extent will the respective groups have achieved gain scores as measured by a pretest/posttest comparison? [2]

Resulting data would provide insight into secondary concerns: To what extent do incoming college preparatory students have knowledge of Latinate word parts and vocabulary? If all groups scored sufficiently high on the pretest, perhaps the use of this strategy would not be justifiable. If one or more groups performed well on the posttest while the remaining did not, this particular strategy may not adequately address the needs of a heterogeneously populated developmental reading class. Finally, if all groups initially performed somewhat poorly yet made significant gains, practitioners desiring to implement a viable vocabulary acquisition component in the curriculum might consider morphological analysis.

Selection of the Population

Non-random samples were derived from students attending a relatively large community college in central Florida. A description of the three distinct groups follows. NES students (n = 44) from three different course sections were enrolled in REA0001 (developmental reading) during one semester. These students were placed into this course based on their results from the Computerized Placement Test (Accuplacer, CPT) administered prior to the commencement of the semester. The CPT is a placement test given to students who have either been out of school for three or more years or whose SAT/ACT scores were deemed too low for admittance into a credit-bearing program of study.

The original number of students from the NES group that had been administered both the pre- and posttest instrument was 54; of these students, the data from 10 students were eventually dropped from the dataset. Four students were self-identified as L2; five others were born in the United States but came from households where English was not the primary language; and the score on one section of the test instrument by one student registered as an outlier. For this latter student, a box plot analysis highlighted this person’s perfect pretest score on the vocabulary section of the test instrument. After one semester of instruction, this student’s posttest vocabulary score was 73. It is the opinion of this researcher that the student’s unusually high score of 100 on the vocabulary portion of the pretest substantiated the limitation of a multiple choice test instrument. Apparently, this student’s guesswork had merely deviated from the norm.

The L2 students were enrolled in EAP1520 (English for Academic Purposes, advanced-level reading). They had either taken the CPT or had followed the sequence of language courses and were now in their highest level of English language instruction prior to full assimilation into an American institute of higher education. Students in this upper level course as well as remedial students in REA both take the same exit reading test that is requisite for admittance into credit-bearing coursework. Only one section of EAP1520 was offered per semester. In order to derive a sufficient sample size, the design was serially replicated. In total, information derived from six consecutive semesters provided an adequate number of LB students (n = 37) and NLB students (n = 51). The LB population initially comprised 38 students. However, one student who had self-identified as French speaking was subsequently found to be equally proficient in Arabic; for the purpose of this study, these language origins were mutually exclusive. Similarly, due to mutually exclusive language origins, one student was exempted from the original NLB population. This latter student was from the Philippines. Though the Philippine language, Tagalog, is NLB in origin, the influence of both Spanish and English in the Philippines raised the issue of confounding effects. The questionable nature of the Romance language influence on Tagalog was apparently warranted as this individual’s pretest and posttest means very closely approximated those of the LB group mean on both sections of the test instrument. Table 1 provides an overview of the specific languages comprising the independent variable.

Table 1. Student Number Based on Language Origin

| Language | NES | LB |

NLB |

Total |

| English | 44 | 44 | ||

| Spanish | 30 | 30 | ||

| French | 4 | 4 | ||

| Portuguese | 3 | 3 | ||

| Russian | 12 | 12 | ||

| Japanese | 11 | 11 | ||

| Korean | 9 | 9 | ||

| Arabic | 5 | 5 | ||

| Hungarian | 3 | 3 | ||

| Gujarati | 2 | 2 | ||

| Serbian | 2 | 2 | ||

| Urdu | 2 | 2 | ||

| Amharic | 1 | 1 | ||

| Czech | 1 | 1 | ||

| Farsi | 1 | 1 | ||

| Macedonian | 1 | 1 | ||

| Thai | 1 | 1 | ||

| TOTALS | 44 | 37 | 51 | 132 |

Setting

All participants attended the same community college in central Florida. For the L2 population, two classes from a spring semester, two classes from a summer semester, and two classes from a fall semester (one class per semester over the course of two years) controlled for the seasonal effect. All courses were held in the same classroom and during the same class days and time for 90 minutes per class, Monday through Thursday, for the duration of 12.5 weeks (environmental control).

NES students (REA0001), in contrast with their L2 counterparts, attended classes in one of three settings. One of the two morning classes was held in the same location where the L2 students attended. This class met Monday and Wednesday for two hours each day. A Tuesday/Thursday class met on a branch campus approximately 30 miles away. The third two-hour class was held in the evenings on Tuesday and Thursday at yet another branch campus that was situated roughly equidistant from the other two campuses. Also, an additional hour per week was scheduled for laboratory time for each of the REA0001 classes. All three of the NES classes were 15 weeks in duration. As with the L2 population, all classes were taught by the same instructor and utilized the same course materials.

Vocabulary and Word Part Instruction

The vocabulary and word part items used in all classes were learned mostly through independent text reading. An outline that consolidated word parts and vocabulary specifically from the text, along with the respective chapter/section/page number, was provided to facilitate content focus; the students were responsible only for those target word parts and vocabulary. A portion of class time was allotted one day prior to each test in order to answer students’ questions. This informal interaction typically lasted from 5-15 minutes. Ethical considerations prevented the researcher from maintaining strict control regarding time allotment for this segment.

In sum, 65 roots were taught, which accounted for 315 distinct words—or approximately 5 words per root. Students were additionally required to utilize inflectional and derivational knowledge in order to correctly identify or produce different word forms based on parts of speech (for example, noun abstraction, noun agent, verb, adjective). Therefore, the amount of potentially different words the student could be expected to know more than tripled the fixed number of words explicitly taught. Students were also taught 42 prefixes and 24 suffixes. Although it may be argued that suffixes infrequently carry intrinsic meaning, the majority of suffixes (17) for this study were chosen because they did, in fact, add meaning to the overall word and did not merely supply the part of speech. For example, the suffix –cide conveys the meaning to kill, as in herbicide and homicide.

Assessment

Ten weekly tests, a comprehensive mid-term, and a comprehensive final examination were administered as a part of ongoing assessment. Each of the ten weekly tests included a review section, which was in keeping with pedagogy that emphasized multiple exposures to the target words and number of retrievals as key components toward facilitating long-term recall (Folse, 1999; Hulstijn, 2001). An item-by-item review with the students was conducted at the conclusion of each weekly test. To review the two major examinations, a computer-generated item analysis highlighted the more troublesome items. These were given priority and addressed in class; subsequently, individual questions for the remaining items were addressed on an as needed basis only. Review of each of the major exams took approximately 15 minutes.

The weekly tests varied in format, for example, item selection, matching, and response generation. Major exams had several sections and each section differed in format, but these tests were exclusively multiple-choice (two to five possible answers per stem). The posttest data-collecting instrument was administered during the last week of class, approximately one week after the final weekly quiz. Also, it was administered one day (or more) prior to the final exam to prevent exposure to the exam from facilitating recall of items on the posttest. Students had not previously seen the results of the pretest, were unaware of which particular items they had answered incorrectly, and were unaware that a posttest was going to be administered.

Data Collecting Instruments

A multiple-choice test instrument (Appendix 1) was used to gather pretest data that determined the extent of students’ existing knowledge of Latinate word parts and Latin-based vocabulary. The same instrument was used again as a posttest to obtain gain scores. Both pretest and posttest mean scores were used to furnish data for later analyses across groups. The instrument consisted of two sections. Section A was comprised of fifteen word parts (ten roots and five prefixes), and Section B was comprised of fifteen vocabulary items. Each of the thirty stems had four possible answers. Word parts and vocabulary were taken from Word Power Made Easy (Lewis, 1978); though an older trade book, its lucid and casual style facilitates a pleasurable read while providing extensive coverage. The same book was used to distinguish word parts as being either a root, prefix, or suffix. Vocabulary items on the test instrument were not to contain word parts found in section A. This was purposely done to discourage students from cross-referencing the two sections of the instrument as an aid to facilitate guessing. However, it was not until far into the research that it was discovered that one vocabulary item, vociferous, also had one of its roots, voc, present in the word part section.

To ensure target vocabulary was commensurate with college coursework, words were reviewed for level of difficulty by using The Living Word Vocabulary (Dale & O’Rourke, 1981). The mean grade level for the 15 vocabulary items used in the instrument was 11th grade with a standard deviation of 2.9. The mode was 13 (n = 5) and the median was 12 (negative skew: mean < median < mode). The vocabulary levels were corroborated with A Revised Core Vocabulary: A Basic Vocabulary for Grades 1-8 and Advanced Vocabulary for Grades 9-13 (Taylor, Frackenpohl, & White, 1969). The mean grade level was 10.6 with a standard deviation of 2.3. Additionally, the mode was 12 (n = 4) and the median was 11; this resulted in a negative skew (mean < median < mode). Apart from the lower mode, the slightly lower mean obtained from the latter reference text was partly attributed to grade level assignments for the individual words. The Taylor et al. text did not identify grade levels beyond college freshmen (grade thirteen) whereas Dale and O’Rourke registered grade level thirteen and then jumped to sixteen; one word, vociferous, was ranked with a grade level of sixteen. This higher number, which was not possible in the other text, partially accounted for the slightly larger vocabulary mean and standard deviation for the Dale and O’Rourke text. Additionally, the Taylor et al. text did not provide data for two of the words used in the pretest/posttest instrument (n =13).

Students recorded their answers to questions from the test instrument on an accompanying computerized scan sheet. A portion of the Scantron above the student’s name was designated for students to write in their primary language and country of origin; this information determined L2 student categorization as either Latin-based or non Latin-based. For the NES group, the same information was solicited along with the additional request asking whether or not a language other than English was spoken at home. Any student from the NES group whose primary language was not English, whose country of origin was not the United States, or whose family spoke a language other than English at home, was excluded from the dataset so as to eliminate any confounding effects. One advantage this researcher had in being the instructor of the course was the familiarity afforded him with the students. This provided the instructor with an opportunity to know students on an individual basis and thus qualitatively verify students’ language origin as self-identified on the Scantron. This proved beneficial in one particular instance where a student had identified herself as LB (French). It was uncovered during the course of the semester that this student had also lived in North Africa and was equally conversant in Arabic. Since, for this study, these respective language origins (LB and NLB) are mutually exclusive, her scores were purged from the dataset.

Results

Following are the comparative means, along with other statistical information, from each of the four datasets obtained from the pretest/posttest comparison. Additionally, tables depicting the gain scores for each level comprising the experiment are provided.

Vocabulary Pretest (Research Question 1a)

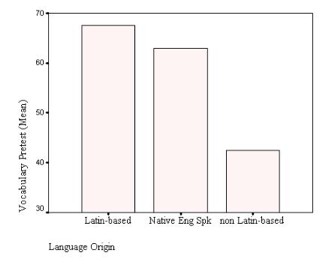

A one-way fixed-factor analysis (SPSS) revealed a significant difference among the means, and Tukey’s b post hoc multiple comparison procedure isolated the non-Latin based mean as distinct from the other group means. NLB’s lower vocabulary pretest mean (42) was statistically significant in relation to the mean of the Latin-based group (68) and that of the native English speaking group (63). Table 2 and Figure 1 display the summaries.

Table 2. Descriptive Data for Vocabulary Pretest (N = 132)

| Language Origin | N | Mean | Median | Standard Deviation |

| LB | 37 | 68 | 67 | 16.7 |

| NES | 44 | 63 | 60 | 15.0 |

| NLB | 51 | 42 | 40 | 18.2 |

Note: LB = Latin-based; NES = Native English Speakers; NLB = Non Latin-based

Figure 1. Vocabulary Pretest Mean Scores for Each Level

Word Part Pretest (Research Question 1b)

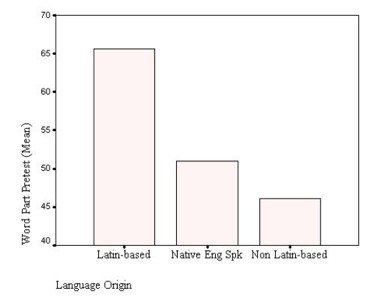

The mean (66) obtained by the Latin-based students on the word part pretest significantly differed from that of the native English speakers (51) and the non Latin-based students (46). Results are displayed in Table 3 and Figure 2.

Table 3. Descriptive Data for Word Part Pretest

| Language Origin |

N | Mean | Median | Standard Deviation |

| LB | 37 | 66 | 67 | 16 |

| NES | 44 | 51 | 47 | 13 |

| NLB | 51 | 46 | 47 | 23 |

Figure 2. Word Part Pretest Mean Scores for Each Level

Vocabulary Posttest (Research Question 2a)

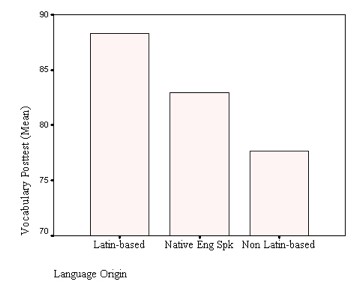

After one semester of instruction and prior to the administration of the final exam, the instrument used as the pretest was administered as a posttest. Results of an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and subsequent multiple comparison procedures (MCP) indicated that all three groups were significantly different from each other. The LB mean derived from the vocabulary posttest was 88, the NES mean was 83, and the NLB mean was 78 (see Table 4 and Figure 3). To obtain better insight into the dynamics behind these numbers, a frequency tabulation was generated (Table 5). An analysis of these data will be taken up in the discussion section of this paper.

Table 4. Descriptive Data for Vocabulary Posttest (N = 132)

| Language Origin | N | Mean | Median | Standard Deviation |

| LB | 37 | 88 | 87 | 8.2 |

| NES | 44 | 83 | 87 | 10.5 |

| NLB | 51 | 78 | 80 | 13.6 |

Figure 3. Vocabulary Posttest Mean Scores for Each Level

Table 5. Frequency Summary for Vocabulary Posttest: All Groups

| Test Score | Frequency (N) | Percent | ||||

| LB | NES | NLB | LB | NES | NLB | |

| 33 | 1 | 2.0 | ||||

| 47 | 1 | 2.0 | ||||

| 53 | 2 | 3.9 | ||||

| 60 | 3 | 5.9 | ||||

| 67 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 2.7 | 13.6 | 7.8 |

| 73 | 2 | 10 | 9 | 5.4 | 22.7 | 17.6 |

| 80 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 16.2 | 11.4 | 27.5 |

| 87 | 12 | 6 | 9 | 32.4 | 13.6 | 17.6 |

| 93 | 10 | 15 | 5 | 27.0 | 34.1 | 9.8 |

| 100 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 16.2 | 4.5 | 5.9 |

| Totals | 37 | 44 | 51 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Word Part Posttest (Research Question 2b)

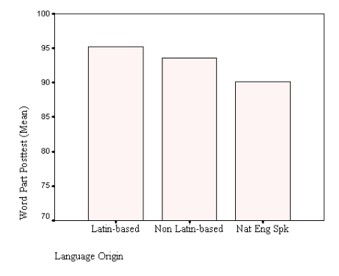

The difference of the NES mean (90) was found to be statistically significant in relation to the NLB mean (94) and the LB mean (95); the data are displayed in Table 6 and Figure 4. With an apparent ceiling effect, the distinction of the NES mean does not appear practically significant; however, insight gleaned from a frequency tabulation (Table 7) points to a dynamic not readily evident from the composite mean scores. This will be addressed in the discussion section.

Table 6. Descriptive Data for Word Part Posttest

Language Origin |

N | Mean | Median | Standard Deviation |

|

| LB | 37 | 95 | 93 | 5.2 | |

| NLB | 51 | 94 | 93 | 7.7 | |

| NES | 44 | 90 | 93 | 7.3 | |

Figure 4. Word Part Posttest Mean Scores for Each Level

Figure 4. Word Part Posttest Mean Scores for Each Level

Table 7. Frequency Data for Word Part Posttest: All Groups

| Test Score | Frequency (N) | Percent | ||||

| LB | NES | NLB | LB | NES | NLB | |

| 67 | 1 | 2.0 | ||||

| 73 | 1 | 1 | 2.0 | 2.3 | ||

| 80 | 1 | 3 | 9 | 2.7 | 5.9 | 20.5 |

| 87 | 4 | 8 | 9 | 10.8 | 15.7 | 20.5 |

| 93 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 40.5 | 29.4 | 36.4 |

| 100 | 17 | 23 | 9 | 45.9 | 45.1 | 20.5 |

| Totals | 37 | 51 | 44 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Gain Scores (Research Question 3)

The final question was posited to investigate the extent of the gain scores for each group on both the vocabulary and word part section on the pretest/posttest comparison. Tables 8-10 show the individual group results while Table 11 presents a comparison of all groups together.

Table 8. Latin-Based (LB) Pretest/Posttest Gain Score Comparisons

| Test Section | Pretest Mean | Posttest Mean | Mean Difference | Standard Deviation | t-Value |

| Vocabulary | 67.6 | 88.3 | 20.7 | 15.3 | -8.2 [a] |

| Word Part | 65.6 | 95.2 | 29.6 | 15.6 | -11.5 [b] |

Note: [a] p < .01, eta squared = .65. [b] p < .01, eta squared = .79

Table 9. Non Latin-Based (NLB) Pretest/Posttest Gain Score Comparisons

| Test Section | Pretest Mean | Posttest Mean | Mean Difference | Standard Deviation | t-Value |

| Vocabulary | 42.4 | 77.6 | 35.2 | 17.4 | -14.4 [a] |

| Word Part | 46.1 | 93.6 | 47.5 | 22.0 | -15.4 [b] |

Note: [a] p < .01, eta squared = .81. [b] p < .01, eta squared = .83

Table 10. Native English Speakers (NES) Pretest/Posttest Gain Score Comparisons

| Test Section | Pretest Mean | Posttest Mean | Mean Difference | Standard Deviation | t-Value |

| Vocabulary | 63 | 83 | 20 | 15.7 | -8.4 [a] |

| Word Part | 51 | 90 | 39 | 15.0 | -17.4 [b] |

[a] p < .01, eta squared = .62. [b] p < .01, eta squared = .88

Table 11. Pretest/Posttest Gain Score Summary: All Groups

| Language Origin | Pretest Mean | Posttest Mean | Gain Score | |||

| Wd Pt | Vocab | Wd Pt | Vocab | Wd Pt | Vocab | |

|

LB

|

66 | 68 | 95 | 88 | 29 | 20 |

| NLB | 46 | 42 | 94 | 78 | 48 | 36 |

| NES | 51 | 63 | 90 | 83 | 39 | 20 |

Note: Wd Pt = Word Part

Data Summary

The results obtained from statistical analyses point to the independent variable, language background, as a key factor in determining significant differences among the three groups comprising this study.

- For the vocabulary pretest, it was found that the NLB mean (42) was significantly lower than the NES and LB means (63 and 68, respectively).

- On the word part section of the pretest, the LB group posted a significantly higher mean score (66) than the NES mean score (51) and the NLB mean score (46).

- Vocabulary posttest scores among the groups significantly differed from each other. The LB mean (88) was approximately five points greater than the NES mean (83), and the NES mean was approximately five points greater than the NLB group mean (78). Secondary findings yielded from a frequency tabulation highlighted a distinctively weaker performance by the NLB group.

- For the word part section of the posttest, it was found that the NES mean score (90) was significantly different from the mean word part score of the NLB group (94) and the LB group (95). Secondary findings derived from a frequency tabulation accentuated the practical significance of these differences.

- The LB group scored highest on all four sections of the test instrument.

- The NLB group scored lowest on three of the four sections of the test instrument.

- Finally, gain scores on both sections of the test instrument were significantly higher for each group involved in the study.

Discussion

First discussed will be specifics related to each research question. General comments about the overall experiment will follow.

Vocabulary Pretest

On the vocabulary portion of the pretest, the NLB group significantly under-performed relative to the other groups. A plausible explanation could be the dissimilarity in form between the orthography of this group and that of English and the Latin-based languages. Many languages comprising the NLB group have an orthography distinct from the symbols used in written English and LB languages (e.g., Spanish). Students from China or Korea would not find immediate parallels between their respective languages and English to facilitate vocabulary comprehension, whereas this problem is obviated for members of the LB group. In fact, though the study of morphology concerns the “meaningful units” of language, the root morph literally means form. It is this stability of form that often carries over in other English derivatives—regardless of differences in pronunciation—and which is often evident in the Latin-based languages. (For literature concerning orthography and second language interference, see Ard & Homburg, 1993; Kaushanskaya & Marian, 2009.)

Additionally, apart from using virtually the same alphabet, Spanish speakers learning English are facilitated by a large number of cognates—vocabulary that is nearly identical between the two languages, such as bank (English) and banco (Spanish). English and Spanish have similar word structures that are based on a shared influence from Latin. The limited visual cues afforded the NLB group could be an important factor behind an increased learning burden evidenced by the significantly lower vocabulary mean.

Similarly, English and the Latinate languages are phonetic in nature. For these languages, letters in the alphabet typically serve as symbols to a corresponding sound (phonemes). For many of the identical letters used both in English and the Latinate languages, the relationship between letters and their sounds is often similar across languages. This is particularly true for the LB sample in this study, which was predominately comprised of native Spanish speakers (30 of 37). Conversely, NLB languages of the world that are phonetic do not have a sound system that corresponds to English, and a few languages utilize a pictographic/logographic writing style rather than a phonetic one (see Wang & Koda, 2005). Therefore, a Spanish-speaking student, for example, would have a relatively easier task of pronouncing an English word by sounding out its constituent parts; this aural aspect can furnish additional clues to assist in word recognition not as easily afforded to the NLB student.

Word Part Pretest

For this section of the pretest, the Latin-based group significantly outperformed the other two groups. As already noted, Latin-based morphemes used in Romance languages often visually resemble the same word parts used in English. LB students that are proficient readers in their L1 may already possess a measure of morphological awareness; this skill could have quite possibly transferred over into their L2.

For the NLB group, the lack of a Latinate component in the Korean and Arabic languages, for example, prohibits students from recognizing word part similarities found in their L1 that could otherwise facilitate second language acquisition. Native English speakers did not fare much better than their NLB counterparts, and scored significantly lower than the LB group. Prior research has suggested that NES college students (non-preparatory) enter higher education with limited skills in morphological analysis (Levin, Carney, & Pressley, 1988; Shepherd, 1973), but the same speculation has not been made, at least prior to this study, regarding L2 students. Perhaps one reason behind the discrepant scores between the NES and LB groups may have to do with academic sophistication. Native English speakers enrolled in college preparatory course work are newcomers to higher education. In contrast, many of the students from the LB group had already earned advanced degrees from institutions in their respective countries. Their exposure to academic content words, albeit in their L1, could have provided them with knowledge of advanced word parts found in morphologically complex vocabulary. This exposure would less likely be afforded to students in the NLB group, regardless of their higher education attainment, due to orthographical interference and the dearth of cognates.

Vocabulary Posttest

No group obtained a mean of 90% or greater on this section of the posttest. This suggests that after one semester of instruction in word parts and corresponding vocabulary, mastery in Latin-based vocabulary is relatively challenging in comparison with word part mastery. (Each group had a mean score of at least 90% on the word part section of the posttest.) The LB group had a mean score five points greater than the NES group while the NES group had a mean score five points greater than the NLB group (88, 83, 78, respectively). Based on the descriptive data, it appears that the independent variable, language origin, played an important role when comparing the LB and NLB groups (a 10-point difference in the means). The relatively large difference between means is most likely explained by the advantage LB students possess when learning English. At least 50% of the English language is based on Latin (Carr, et al., 1942; Shepherd, 1973); this should prove advantageous for students whose language background is Latinate. Spanish speakers can readily discern that the Latin root viv evidently means life, as many Spanish words are based on this root (the verb to live is vivir). Thus, members of the LB group would find it comparatively easy to utilize this base to learn and subsequently recall the meanings of English words such as vivacious (lively) and vivify (to make alive).

The three significantly distinct posttest vocabulary means do not call adequate attention to the relative strength of the LB group nor the relative weakness of the NLB group. The frequency tabulation compiled in Table 5 was useful in isolating extreme scores, which in turn highlighted relative strengths and weaknesses. On the high end of the scale, slightly over three quarters of the LB students scored over 80% on the vocabulary posttest; slightly over half of the NES students did the same. In comparison, only one third of the NLB students yielded a score over 80% after one semester of instruction. Comparing the three groups by highlighting their low scores accentuated the same disparity. On the low end of the scale, not one student from either the LB group or the NES group scored 60% or less, whereas 7 NLB students (14%) did.

The overall lower mean of the NLB group was not attributed to extremely low scores obtained by only a few students, thus skewing the mean. With 14% of the NLB group scoring poorly and only one third scoring over 80%, the data suggest that this particular group had the most difficulty mastering explicit vocabulary. This may have implications for practitioners with regard to monitoring the progress of students from non Latinate backgrounds. Second language interference (e.g., orthography and phonics) is one possible explanation. With less of a Latinate repertoire to draw upon, there are fewer language schemata to facilitate recall.

Word Part Posttest

The difference of the NES mean (90) in comparison to the NLB (94) and the LB mean (95) was statistically significant. Descriptively, the data did not appear to suggest any difference of practical significance; in fact, all three groups had the same median—93. Another perspective was afforded through use of a frequency tabulation (Table 7). This display revealed a distinction specific to the NES group. By isolating extreme scores, it was evident that certain members of the NES group did not perform as strongly as their peers. On one end of the spectrum, relatively low scores (≤ 80%) were obtained by nearly 23% of the NES group in contrast with only 10% of the NLB group and less than 3% of the LB group. At the high end of the range, a full ceiling effect of 100% was obtained by only 21% of the students in the NES group in contrast with 45% of students in the NLB group and 46% of the students in the LB group. Stated differently, members of the NES group were more than twice as likely to score poorly in comparison with the NLB group, and more than eight times as likely to score poorly in comparison with the LB group. At the other end of the spectrum, students from the LB and NLB groups were twice as likely to obtain a perfect score in comparison to the NES group.

Factors such as student motivation and study habits that had not been controlled for could have quite possibly affected the results. The researcher of this study was the instructor for all classes; this provided the researcher with a vantage point to qualitatively observe facets not revealed via quantitative measures. It was observed that members from both subgroups comprising the L2 population often displayed greater interest in the subject matter than certain members from the NES group as indicated by the amount and types of questions asked by these students, quantity and quality of homework performed, and the number of students along with their frequency in attending after-class tutoring. Part of this could be attributed to student goals. For some NES students, this course could be seen as a class they “have to” take due to failure on the CPT. Though obligatory, their eye is on the credit bearing courses to come; vocabulary is merely part of the required class work in a course they did not elect to take. However, for the L2 students, learning vocabulary would be high on their list of priorities. For those going on to higher education in an English-only environment, mastering the language is crucial. In sum, the NES group appears to be dichotomized between a segment that mastered word parts, and a segment that did not; scores posted by the ELLs were more homogeneous.

Gain Scores

Overall, each group made significant gains on both sections of the test instrument from pretest to posttest. Gains were greater on the word part section of the test instrument than on the vocabulary section. In part this may be due to the ubiquitous nature of word parts as one part may be found in many words, thus affording more exposure for recall. Additionally, word parts are less abstract and more unitary in meaning than vocabulary items, lessening their complexity. All groups made significant progress over the span of one semester, which attests to the use of morphological analysis as a viable strategy.

General Comments

Identifying groups within the college preparatory reading class based on language origin brought to light distinctive strengths and weaknesses relative to L1 status. This is important since all of the students involved in this study were placed into the same course level based, theoretically, on similar reading ability. Although data in this study are composite from two distinct courses (L1 from developmental reading and L2 from an English Language Institute), it is not unusual for both L1 and L2 students to occupy the same developmental reading class. At the time of this publication, a number of community colleges in the state of Florida did not have a language institute to address the academic needs of ELLs, or in some instances where colleges had such a program, upper level coursework was not offered. In the case of the latter, students completing the highest level of L2 instruction were funneled into developmental tracks for reading and writing.

Summary

First, of the three distinct groups, students comprising the LB group performed the strongest as evidenced by having scored the highest on all four sections of the test instrument. However, on only one of the four comparisons did the LB group obtain a statistically significant difference. This was observed on the word part section of the pretest (LB mean = 66, NES = 51, NLB = 46).

Second, the NLB group demonstrated the greatest weakness among the levels. This group scored the lowest on three out of the four possible group comparisons, and on the vocabulary pretest, the NLB mean difference was statistically significant (NLB = 42, NES = 63, LB = 68).

Third, the prominent distinction evidenced by the NES group was its statistically significant lower word part posttest score (NES = 90, NLB = 94, LB = 95). Though not practically evident through the descriptive statistics, isolating extreme scores through a frequency tabulation demonstrated a dichotomization within the NES group between those going on to mastery and those performing at a disproportionately low level.

Finally, each group mean on both sections of the pretest instrument was relatively low, yet each group mean on both sections of the posttest was significantly higher. The pretest data demonstrate a need for vocabulary enhancement and word part awareness among college preparatory students. Posttest data suggest that morphological analysis as a vocabulary acquisition and retention strategy can benefit college preparatory students irrespective of their language origin.

Conclusion

Morphological analysis was chosen as the particular vocabulary acquisition strategy incorporated into several reading courses at a community college in central Florida. Significant gain scores among all the levels suggest that this strategy is robust enough to be used in today’s heterogeneously populated developmental courses. A strategy usage survey by Schmitt (1997) revealed that as students matured (middle school through adult), they became increasingly averse to using certain strategies while increasingly inclined to using morphological analysis. Based on the trend apparent in his survey, Schmitt concluded, “Given the generally favorable response to strategies utilizing affixes and roots, both to help discover a new word’s meaning and to consolidate it once it is introduced, it may be time to reemphasize this aspect of morphology” (p. 226).

This has important implications for the preparatory student since morphologically complex words are more prone to occupy the collegiate arena. Just and Carpenter (1987) reported that the use of morphological analysis was more likely to be used correctly with infrequent words—words of Classical origin (Greek and Latin)—than with frequent words. Oldfather (1940) demonstrated that Latin was deemed as a living language and would continue to contribute to the English lexicon. A perusal of the test instrument illustrates that the vocabulary chosen was not comprised of obscure items of little use to the reader. Neither was the level of difficulty for these words too great. The mean vocabulary level, identified by Dale and O’Rourke (1981) and verified by Taylor, Frackenpohl and White (1969), was roughly grade eleven. Consequently, morphologically complex vocabulary taught at the college preparatory level along with a working knowledge of morphemes has potential to offer an important contribution toward students’ college readiness.

The fact that not one of the groups registered a score better than 68%[3] on either section of the pretest indicates that direct instruction of a vocabulary acquisition strategy of some sort is warranted. College preparatory students it appears, regardless of their language origin, enter the community college with limited knowledge of word parts and the Latinate college level vocabulary comprising those word parts. These findings mimic what was formerly stated regarding college freshmen in general (Levin, Carney, & Pressley, 1988; Shepherd, 1973) and are now empirically substantiated, at least with this sample, for college preparatory NES students and ELLs.

Results from this quasi-experimental study point to justification for the creation of at least two separate developmental reading courses. (Cut-off scores from the CPT may serve to differentiate placement.) Though some colleges presently provide multiple levels, others provide only one level of developmental instruction. As results from this study underscore, students in the NES group were dichotomized between those who “got it” and those who did not. The NLB group had the most difficulty as a whole. Perhaps certain students from these groups, as well as some from the LB group, may be better served in a lower, more fundamental class.

The use of morphological analysis is not without its critics. Much of the criticism can be assuaged when such a strategy is streamlined to ensure that only salient components and a research-based methodology are applied. The requisite criteria for using morphological analysis successfully and a detailed explanation of one particular methodology employed have been articulated elsewhere (Bellomo, 2009).

About the Author

Tom Bellomo is an associate professor at Daytona State College, Florida. He taught in the college’s English Language Institute for nine years, and now teaches reading and writing in heterogeneous (L1 & L2) classes in the school of Humanities and Communication. Additionally, he teaches graduate level Applied Linguistics for Stetson University.

Notes

[1] A one-way fixed-factor ANOVA (used when comparing more than two means) was used to assess whether or not significant differences existed among the variables. Though it indicates significance, a follow up (post hoc) procedure must then be employed to identify which one(s) significantly differ(s). Tukey’s b post hoc multiple comparison procedure (for unequal sample sizes) was used to identify the significantly different dependent variable(s). The alpha level for all analyses was set at .05. Both the ANOVA and Tukey’s b were incorporated into the first two research questions.

[2] A dependent samples t-test (used when comparing two means) was used to conduct three separate analyses.

[3]Scores are for the most part inflated due to the nature of multiple choice testing. Students receive credit for every item they know, but for each remaining unknown item, there exists a 25% possibility of correctly guessing the right response.

References

Ard, J., & Homburg, T. (1993). Verification of language transfer. In S. Gass & L. Selinker (Eds.), Language transfer in language learning (pp. 47-70). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Beck, I. L., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2002). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction. N. Y.: Guilford Press.

Bellomo, T. (1999). Etymology and vocabulary development for the L2 college student. TESL-EJ, 4(2), 7 pp. Retrieved July 5, 2008 from http://tesl-ej.org/ej14/a2.html.

Bellomo, T. (2009, April). Morphological analysis and vocabulary development: Critical criteria. Reading Matrix, 9(1), 44-55: http://www.readingmatrix.com/articles/bellomo/article.pdf.

Biemiller, A., & Boote, C. (2006). An effective method for building meaning vocabulary in primary grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(1), 44-62.

Carr, W. L., Owen, E., & Schaeffer, R. F. (1942). The sources of English words. The Classical Outlook, 19(5), 455-457.

Carver, R. P. (1994). Percentage of unknown vocabulary words in text as a function of the relative difficulty of the text: Implications for instruction. Journal of Reading Behavior, 16, 413-37.

Corson, D. (1997). The learning and use of academic English words. Language Learning, 47(4), 671-718.

Dale, E., & O’Rourke, J. (1981). The living word vocabulary: A national vocabulary inventory. Chicago: Worldbook – Childcraft International.

Davis, F. B. (1944). Fundamental factors of comprehension in reading. Psychometrika, 9(3), 185-197.

Davis, F. B. (1968). Research in comprehension in reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 3(4), 499-545.

Ebbers, S., & Denton, C. (2008). A root awakening: Vocabulary instruction for older students with reading difficulties. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 23(2), 90–102.

Folse, K. S. (1999). The effect of the type of written practice activity on second language vocabulary retention. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of South Florida.

Folse, K. S. (2004). Vocabulary myths: Applying second language research to classroom teaching. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Hulstijn, J. (2001). Intentional and incidental second language vocabulary learning: A reappraisal of elaboration, rehearsal and automaticity. In M. H. Long and J. C. Richards (Series Eds.) & Robinson, P. (Vol. Ed.), Cognition & Second Language Instruction (pp. 258-286). Cambridge: University Press.

Just, M. A., & Carpenter, P. A. (1987). The psychology of reading language comprehension. Newton, MA: Allyn and Bacon, Inc.

Kaushanskaya, M., & Marian, V. (2009). Bilingualism reduces native-language interference during novel-word learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 35(3), 829–835.

Laufer, B. (1997). The lexical plight in second language reading: Words you don’t know, words you think you know, and words you can’t guess. In M. H. Long & J. C. Richards (Series Eds.) & Coady, J & Huckin, T. (Vol. Eds.), Second language vocabulary instruction (pp. 20-34). Cambridge: University Press.

Levin, H. M., & Calcagno, J. C. (2008). Remediation in the community college: An evaluator’s perspective. Community College Review, 35(3), 181-207.

Levin, J. R., Carney, R. N., & Pressley, M. (1988). Facilitating vocabulary inferring through root-word instruction. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 13, 316-322.

Lewis, N. (1978). Word power made easy: The complete handbook for building a superior vocabulary. NY: Pocket Books.

Lowman, J. (1996). Assignments that promote and integrate learning. In R. Menges & M. Weimer (Eds.), Teaching on solid ground: Using scholarship to improve practice (pp. 203-231). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

McCutchen, D., Green, L., & Abbott, R. (2008). Children’s morphological knowledge: Links to literacy. Reading Psychology, 29, 289-314.

Nagy, W., Berninger, V., & Abbott, R. (2003). Relationship of morphology and other language skills to literacy skills in at-risk second-grade readers and at-risk fourth-grade writers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(4), 730-742.

Nagy, W. E., & Herman, P. A. (1987). Breadth and depth of vocabulary knowledge: Implications for acquisition and instruction. In M. G. McKeown & M. E. Curtis (Eds.), The nature of vocabulary acquisition (pp. 19-35). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Oldfather, W. A. (1940). Increasing importance of a knowledge of Greek and Latin for the understanding of English. Kentucky School Journal, 37-41.

Reed, R. K. (2008). A synthesis of morphology interventions and effects on reading outcomes for students in grades K-12. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 23(1), 36-49.

Schmitt, N. (1997). Vocabulary learning strategies. In N. Schmitt & M. McCarthy (Eds.), Description, Acquisition and Pedagogy (pp. 199-227). Cambridge: University Press.

Shepherd, J. F. (1973). The relations between knowledge of word parts and knowledge of derivatives among college freshmen. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, New York University.

Stahl, S. A. (1982). Differential word knowledge and reading comprehension. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Harvard University.

Stahl, S. A. (1990). Beyond the instrumentalist hypothesis: Some relationships between word meanings and comprehension. (Tech. Report No. 505). University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign, Center of the Study of Reading.

Taylor, S. E., Frackenpohl, H., & White, K. W. (1969). A revised core vocabulary: A basic vocabulary for grades 1-8 and advanced vocabulary for grades 9-13. EDL Research & Information Bulletin 5. Huntington, NY: Educational Developmental Laboratories.

Wang, M., & Koda, K. (2005). Commonalities and differences in word identification skills among learners of English as a second language. Language Learning, 55(1), 71-98.

| © Copyright rests with authors. Please cite TESL-EJ appropriately.

Editor’s Note: The HTML version contains no page numbers. Please use the PDF version of this article for citations. |

Appendix 1: Pretest/Posttest Instrument

Word Parts & Vocabulary

Do NOT write on this sheet; record all answers on Scantron only.

Word Parts (A):

For each of the following word parts, choose the correct definition/synonym from the four given options.

| 1) cap/capt: | a) rug | b) keep | c) head | d) truth |

| 2) bene | a) old | b) good | c) false | d) humorous |

| 3) dict | a) alphabet | b) copy | c) short | d) speak |

| 4) scrib | a) work | b) write | c) shout | d) fast |

| 5) man/manu | a) hand | b) horse | c) masculine | d) intelligent |

| 6) ject | a) handsome | b) throw | c) foolish | d) outward |

| 7) vit/viv | a) alive | b) two | c) speech | d) right |

| 8) noc; nox | a) sick | b) nose | c) sad | d) night |

| 9) voc; vox | a) kiss | b) fast | c) voice | d) short |

| 10) cred | a) belief | b) government | c) card | d) lost |

Word Parts (B):

For each of the following word parts, choose the correct definition/synonym from the four given options.

11. sub:

a) rise up b) under c) lie down d) away

12. post:

a) with strength b) after c) containing holes d) large

13. in:

a) below b) not c) never d) last

14. com:

a) with b) alone c) whole d) false

15. pre:

a) early b) before c) old d) stop

Vocabulary:

Each of the vocabulary words below is followed by one correct definition/synonym. Choose the response (a, b, c, or d) that best depicts the meaning of the italicized vocabulary word.

16. magnanimous:

a) not happy b) strong c) generous d) book smart

17. gratify

a) to grow b) to please c) to lie d) to fight

18. spectacle

a) lost in space b) falling star c) a show d) of little value

19. fidelity

a) trusted b) finances c) war hero d) disorder

20. pedestrian

a) a walker b) politically incorrect c) politically correct d) a wheel

21. vociferous

a) weak-minded b) easy c) difficult d) loud outcry

22. parity

a) festivity b) lightness (weight) c) shortness (distance) d) fairness

23. potent

a) angry b) pretty c) powerful d) ugly

24. vivacious

a) funny b) not honest c) lively d) always late

25. retrospect

a) to look back b) small particle of dust c) sleep often d) to retire

26. unanimous

a) hateful of animals b) kind toward animals c) suspicious d) all agree

27. herbicide

a) little energy b) kills plants c) extreme illness d) talkative

28. ambivalent

a) two arms b) conflicting feelings c) loving; romantic d) violent

29. gregarious

a) talkative b) gracious c) dangerous d) sociable

30. omniscient

a) lover of science b) everywhere c) all knowing d) egg-shaped