March 2010 — Volume 13, Number 4

** On the Internet **

Twitter Fiction: Social Networking and Microfiction in 140 Characters

Carla Raguseo

Universidad del Centro Educativo Lationamericano, Argentina

carlaraguseo gmail.com

gmail.com

Introduction

The Web as an interactive open publishing platform

Since the turn of the 21st century the web has evolved from a vast source of information into an ever growing multimedia platform–Web 2.0 or Read-Write Web–that allows users to share, (co-) create, (co-) author and (co-) edit digital content. This paradigm shift implies a new role for the user from a mere consumer to an active producer or prosumer (Hemetsberger and Pieters, 2001-2003). The OECD has proposed the following characterization of “User-Generated Content” or “Consumer-Generated Media”:

1) Content made publicly available over the Internet, 2) which reflects a certain amount of creative effort and 3) which is created outside of professional routines and practices. (OECD, 2007)

These technologies that enable internet users, not only to access, but also to contribute content, are responsible for a revolution in the way information is created and distributed (Ochoa & Duval 2008, p. 19). Therefore, this significant change goes far beyond its technological dimension, having a profound effect on the social, political, educational and cultural spheres.

At the core of these developments, social networks facilitate connections, instant communication, and multimedia format sharing worldwide, making it even easier for users to interact and spread digital content on the web in real time. These users build up their profiles, publishing personal information together with photos, video, images, audio, and blogs, from which they are able to connect with friends and colleagues or meet new people. On the academic side, a large body of knowledge has accumulated on the formation and dynamics of these networks, fueled by the easy availability of data and the regularities found in the statistical distribution of nodes and links within these networks (Huberman, Romero, & Wu 2008, p. 2).

Among the most influential Web 2.0 applications, Twitter is a social network and microblogging service that allows users to publish status updates, called tweets, of up to 140 characters, which are distributed to subscribed followers by instant messages, mobile phones, email or the Web. All followees’ updates, in turn, are displayed on a personalized Twitter stream which constitutes the user’s home page. According to Evan Williams, Twitter CEO, user involvement in Twitter has gone as far as creating a specific syntax to reply to specific users (Williams, 2009). Developers later built in this feature as an enhanced automatic function. Huberman, Romero and Wu provide the following description:

Twitter users are able to publicly post direct and indirect updates. Direct public posts are used when a user aims her update to a specific person and are signaled by an “@” symbol next to the person’s username, whereas indirect updates are used when the update is meant for anyone that cares to read it. Even though direct updates are used to communicate directly with a specific person, they are public and anyone can see them. Often times two or more users will have conversations by posting updates directed to each other. (2008, n.p.)

Although it was initially conceived as just a social medium for electronic communication, some users have stretched the limits of the medium and have now transformed Twitter into an open publishing platform for microfiction.

Background: User-Generated Fiction on the Web

With the advent of the Web in the early 1990’s electronic bulletin boards and online databases provided users with the ability of self-publishing fan fiction. FanFiction.net is a well known site for literary publications where users contribute and review stories inspired in existing, professional-generated, books, TV series or movies (Ochoa & Duval, 2008, p. 19). In addition, authors could communicate with other authors and readers through forums and chat rooms (OECD, 2007).

Later on, blogs and wikis offered a space for easy publishing and collaboration, which also allowed interaction between readers and writers.

Fiction on Twitter

Among some of the literary projects that have been developed on Twitter since its appearance in 2006, we can mention

- the Rayuela Project (http://twitter.com/rayuela/) in Spanish, which is currently publishing Cortazar’s book in daily updates

- Booktwo (http://twitter.com/booktwo/) in English, broadcasting James Joyce’s Ulysses for its Twitter followers

- Twittories (http://twittories.wikispaces.com), in which a group of authors writes short stories collaboratively, each one adding one 140-character entry

- The Story So Far (http://cwd.co.uk/storysofar/), in which well-known books are re-told in shorter versions taking only the first line of the original. This would constitute an updated 2.0 version of FanFiction.net.

Twitter Fiction

Perhaps the most relevant development for language learning is the production of microfiction stories on a microblogging platform. Unlike the previous examples, Twitter fiction refers to an original, self-contained work of fiction in each tweet published by a Twitter user.

As regards the format of microstories, the 140-character space limitation has generated two approaches, with some authors, like Arjun Basu, writing stories of exactly 140 characters, while others simply consider it as a limit instead of a structural constraint and may write 140 characters or less. Twitter Fiction writer Chris Brauer expresses his preference for the latter:

One of the most demanding early questions is whether you should post stories of exactly 140 characters or write stories of 140 characters or less. This has a big practical impact on the process as if you decide on the former you often find yourself writing to conform to the strict format instead of letting the creative process drive the length. It really is the difference between writing free-form poetry and iambic pentameter or haikus. (2009, n.p.)

In contrast to other pieces of microfiction, due to the characteristics of the entry window or text box, Twitter stories do not have a title, which is an element that provides a focus or completes the meaning of the story (Lagmanovich, 2006). This feature, therefore, emphasizes their fragmentary presentation. On the author’s profile, all tweets are displayed in reverse chronological order and are distributed that way to his or her network.

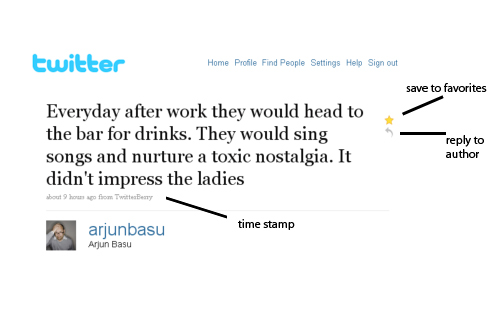

Figure 1. Twitter Author Profile

Another structural consideration is the automatic time stamp published in every tweet which gives us a sense of immediacy and also provides a permanent link to the entry for easy reference and retrieval. In addition, Twitter gives users the possibility of saving “favorite tweets” and replying to authors by using the @+username function.

Figure 2. Tweet with Timestamp

In spite of the hybrid nature of microfiction, Twitter fiction is being classified into or labeled by its authors with certain literary genres which are given new names by combining the name of the different genres with the name of the application (portmanteau words). Thus, thrillers become twillers, haikus, twaikus and short stories, twistories or twisters.

As an expression of experimental postmodern literature, Twitter fiction shares characteristics of printed microfiction, such as brevity, multiple meanings, intertextuality, and fragmentarism (Zavala, 2009), reflecting the very nature of the environment in which it is produced.

As can be seen in the examples below, these characteristics blend in playful literary experimentation by both professional authors and amateur writers who choose to publish and share their productions on the web. The following samples of Twitter fiction are also characterized by a rich lexical density, metafictive devices, and even code-switching, revealing their complexity and multiple literary and extra-literary dimensions:

The wolf grins. “Sweet girl, why are you on the nightpath alone?” I smile with teeth, grip my knife under the red cloak. “Come find out.” (137 characters)

4:40 PM Aug 15th from thaumatrope (By Thamatrope)

He knew it. Sensed it. A dreadful feeling shot up to his mind just a moment before she spoke. It was over. Her husband knew. He had to hide. (140 characters) 2:11 PM Mar 24th, 2008 from web (by Twitterfiction)

250. La única posibilidad es huir, dices. Eso es para cowards, repito inútilmente cuando vamos ya a medio camino. Atrás, pequeños delirios. (134 characters) 3:31 AM Aug 7th from web (by Microtxts)

When the caveman lay on the stone to sleep, bizarre and wonderful ideas entered his mind before his dreams. Pen-less, he lost them. (131 characters)

2:05 AM Aug 17th from web (by Midnightstories – Ben White)

They scattered his ashes. The wind turned, blew the stinging ash into their eyes. “He always had to have the last word,” his wife mumbled. (138 characters) 4:01 PM Aug 26th from API (by Nanofiction)

Dramatic music. He is struck by lightning. She comes rushing out. Drags him inside. They fall in love before he dies. Dramatic music swells. (140 characters) 11:49 AM Aug 22nd from TwitterBerry (by Arjun Basu)

His small town felt too small. So he went to the big city. And he found a lousy job. And a tiny apartment. And moved back to his small town. (140 characters) 11:29 AM Aug 16th from TwitterBerry (by Arjun Basu)

Frank climbed the mountain and the old man on top said, Life is an illusion. And Frank punched the old man in the face and watched him bleed (140 characters) 2:58 PM Sep 1st from Seesmic (by Arjun Basu)

Dissemination Strategies on Twitter

With a dynamic, unbounded, ever growing amount of digital content spreading across networks, users need to develop new e-skills and strategies to be able to select, process and make sense of the information around them. Tags are a central concept to understanding how information management works on the web.

A working understanding of aggregation, tagging, and RSS (Really Simple Syndication) is key to collaboration as well as to filtering and regulating the flow of information resources online. Tags allow people to organize the information available through their distributed networks in ways that are meaningful to them, and social networking enables nodes in these networks to interact with each other according to how these tags and other folksonomic […] data overlap. (Stevens et al., 2008, p. 1)

Similarly, with the proliferation of authors of microfiction on Twitter, users have had to resort to specific in-built functions to be able find, collate and interact with these stories, their writers, and other readers. Tags on Twitter are called hashtags and are signaled by a “#” symbol followed by the label or key word. Twitter users who only occasionally write microstories add some of the following tags to their tweets for other people to be able to find them:

- #vss (stands for very short story)

- #microfiction

- #flashfiction

- #twiction

- #twisters

- #nanofiction

- #micromemoir

Additionally, other users may cite or retweet these authors by using the RT@+username feature, allowing, as Stevens points out, nodes to expand and interact across networks.

In November 2009, a new retweet system was made gradually available to users, making it possible to retweet stories of exactly 140 characters automatically without using the previous RT feature which took up character space.

Twitter lists are a new feature which allows users to manage their followees and group them according to specific criteria. Therefore, through the use of lists, users may create individual streams consisting of their favorite Twitter authors without having to follow them or receive their tweets on their home page.

Interestingly enough, lists have also allowed for the appearance of an ambitious form of multi-user Twitter Fiction such as State of Normal (http://twitter.com/state_normal/characters/). Users can follow the twitterized story through its character list, where the plot unfolds in real time through the characters’ interactions. In addition, this networked storytelling experience is built across platforms, since it has a Twitter account for extra information, reactions, and summaries; as well as a blog and a website with detailed information about every character and every setting in the town of “Normal,” plus a script archive.

Figure 1. The State of Normal

Other Digital Publication Formats

The interest aroused by Twitter fiction has caused some users to create special Twitter profiles, such as Nanoism (http://twitter.com/nanoism/), Nanoed (http://twitter.com/nanoed/) or Microtxts (http://twitter.com/microtxts/) to compile and spread the work of disseminated authors on the network. Other projects include the publication of submitted Twitterfiction on blogs called Twitterzines (http://nanoism.net) and contests that aim at the publication of Twitterfiction e-books (http://crossfadernetwork.wordpress.com/2009/08/12/e-life-remix-project/).

Twitter Fiction in the EFL classroom

Many of the Twitter Fiction accounts mentioned throughout this article (e.g., Very Short Story http://twitter.com/VeryShortStory/) could prove engaging reading activities for EFL students, since microfiction calls for the reader’s full awareness and collaboration. In order to “read” these microstories students need to interpret, infer, complete and recreate the texts to “construct” their meaning.

In every story the relationship between the beginning and the ending is a crucial element. In modern and post modern microfiction the beginning is enigmatic, i.e. anaphoric, in medias res […] while the ending is a mock ending, i.e. cataphoric, incomplete [..] (Zavala, 2007)[1]

The author concludes that this has a pragmatic consequence for readers: it motivates them to re-read the text.

The following are examples of some Twitter Fiction experiences currently being carried out that can be joined, replicated, or adapted to the language classroom:

- Complete da tweet http://twitter.com/CompleteDaTweet/

- Sixwordstories http://twitter.com/sixwordstories/status/10048534239/

- Name your tale: http://twitter.com/NameYourTale/

- Misquotable http://twitter.com/Misquotable/

Whether the idea is to complete a one-line story following a given prompt, write a microstory in just six words, or recreate a well-known quotation, students need to develop deep syntactic and lexical awareness to construct meaning under such spacial and/or structural constraints.

Literature Tweets

One of the most compelling turns of Twitter in literature is the creation of profiles for literary characters or famous writers. We can surely gain an insight into the nature of all-time literary classics by reading their anachronistic or imaginative tweets as they interact with other users.

- http://twitter.com/MissJoMarch/ (Jo March – Little Women)

- http://twitter.com/justagoverness/ (Jane Eyre)

It can provide interesting ground for discussion, reflection and discovery to read William Shakespeare’s reactions to contemporary events or Edgar Allan Poe “tweeting from his tomb.”

What’s more, these types of “character tweeting” can help us interpret and rediscover characters and writers by approaching their inter-textual game in a real time, interactive digital environment.

In his “Twenty-Five Interesting Ways To Use Twitter in the Classroom,” Sauers (2009) included some historical, literary and fiction-related uses suggested by other Twitter users that can be particularly suitable for the EFL classroom, such as:

- Produce a tweet dialogue between two opposing characters (e.g., King Harold and William the Conqueror) about a key issue (@russeltarr)

- Tweetstories: tweet a standard story opener to your network. Ask the network to continue the story in tweets, collaborating with the previous tweets and following them via http://www.twitterfall.com or a #tag (@kevinmulryne)

- Short but sweet: Give children individually the twitter 140 characters rule – they have to write a story introduction, character description, or a whole story. (@kevinmulryn)

- Point of View and Character Development

- Based on a novel or short story

- After a study of point of view and character development, students become a character and create a twitter account ex: @janeeyre, @rochester

- Students use their study of that character to create conversations around key events in the plot

- Students might focus on events and situations that are omitted from the text, but referred to, so the students are creating their own fiction based on their knowledge of the writer, the time period, and the characters (@hlvanrip)

- Based on a novel or short story

All in all, Twitter fiction can provide learners with a rich language experience in easily digestible fragments. It challenges them both as readers and as writers to attempt and explore multiple meanings and to develop academic skills such as synthesizing and paraphrasing while fostering structural and semantic awareness in playful experimentation.

Furthermore, microstories, misquotes and historical tweets are rich in cultural and literary references, and as such present a wide range of learning opportunities. They can help achieve the aim of teaching English through content that is dynamic, relevant and exciting for students.

Zavala (2007) has pointed out that microfiction is the antivirus of literature since it has the following effects in those who read it (as translated by the author):

- It is a vaccine that causes children and inexperienced readers to become addicted to literature

- It allows easy access to huge works by approaching the fragment.

- It provides a didactic way to learn about complex literary elements, such as: humor, irony, parody, allusion, allegory and indeterminacy.

- It blurs the distinction between reading and interpreting a text.

Surely, the same can be said about Twitter Fiction. In addition, Twitter’s networked nature facilitates connections, collaboration and immediate feedback for students’ productions while building and generating interactions with a worldwide audience.

Towards open participatory literary circles

Current information and communication technologies such as Twitter harness the weightless materialization and viral dissemination of new forms of literature in which the voice of readers and writers blend in participatory interconnected digital literary circles. The participatory architecture of the Web 2.0 has allowed the creation and dissemination of user-generated content, which takes different social, cultural and literary forms.

Far from belonging to a unified scholarly literary movement, Twitter fiction has emerged haphazardly from individual and collaborative experiments on the web. Its diversity can be illustrated in terms of a wide variety of genres that range from short stories and thrillers to haiku-style poems. In addition, the phenomenon has spread beyond its original web application to other electronic publications such as twitterzines and e-books. As we have seen, it may also provide a compelling reading and writing experience for EFL students, while introducing them to a contemporary literary form.

About the Author

Carla Raguseo is an EFL teacher at Universidad del Centro Educativo Lationamericano (UCEL) and at Instituto Politécnico Superior in Rosario, Argentina. She has experience as multimedia lab coordinator, e-learning course designer, and tutor. She blogs professionally at: http://carlaraguseo.edublogs.org.

Note

[1] An earlier version of this paper was presented at the III National Conference on Microfiction in Spanish and in English held at UCEL on October 9th and 10th, 2009 in Rosario, Argentina.

References

Brauer, C. (2009). Twitter fiction and short stories. Retrieved March 26, 2010 from http://www.chrisbrauer.com/weblog/2009/04/twitter-fiction-and-short-stories.php.

Hemetsberger, A. & Pieters, R. (2001). When consumers produce on the Internet: An inquiry into motivational sources of contribution to joint-innovation. In Derbaix, C., Kahle, L., Merunka, D., & Strazzieri, A. (eds.). Proceedings of the Fourth International Research Seminar on Marketing Communications and Consumer Behavior, (pp. 274-291). IAE Aix-en-Provence: The La Londe Seminar 28th International Research Seminar in Marketing.

Huberman, B., Romero, D., & Wu, F. (2008). Social networks that matter: Twitter under the microscope. Labs HP Research. Retrieved March 26, 2010 from http://www.hpl.hp.com/research/scl/papers/twitter/.

Lagmanovich, D. (2006). La extrema brevedad: Microrrelatos de una y dos líneas. [Extreme brevity: Microrrelates of one and two lines] Espéculo. Revista de estudios literarios. Retrieved March 26, 2010 from http://www.ucm.es/info/especulo/numero32/exbreve.html.

Ochoa, X. & Duval, E. (2008). Quantitative analysis of user-generated content on the Web. Proceedings of the First International Workshop on Understanding Web Evolution (WebEvolve2008), 22 Apr 2008, Beijing, China, ISBN 978 085432885 7, pp. 19-26. Retrieved March 26, 2010 from http://journal.webscience.org/34/.

OECD. (October 2007). Participative web and user-created content: Web 2.0, wikis and social networking. OCDE Information Sciences and Technologies. Retrieved March 26, 2010 from http://www.oecd.org/document/40/0,3343,en_2649_34223_39428648_1_1_1_1,00.html.

Sauers, M. (2009). Twenty-five interesting ways to use Twitter in the classroom. Retrieved March 26, 2010 from http://www.slideshare.net/travelinlibrarian/twenty-five-interesting-ways-to-use-tw.

Stevens,V. Quintana, N., Zeinstejer, R., Sirk, S., Molero, D., & Arena, C. (2008). Writingmatrix: Connecting students with blogs, tags, and social networking.” TESL-EJ, 11.4. Retrieved March 26, 2010 from http://www.tesl-ej.org/wordpress/past-issues/volume11/ej44/ej44a7/.

Williams, E. (2009). Twitter, origen y evolución: Evan Williams en TED 2009. [Twitter: Origin and evolution: Evan Williams at TED 2009] Retrieved March 26, 2010 from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I-U3jgY6vds.

Zavala, L. (2007). De la teoría literaria a la minificción posmoderna. [From literary theory to postmodern minifiction] Ciências Sociais Unisinos, 43(1), 86-96.

Zavala, L. (2009).Los estudios sobre minificción: Una teoría literaria en lengua española. [Studies of microfiction: A Spanish-language literary theory] El Cuento en Red Revista electrónica de teoría de la ficción breve, 19. UAM Xochimilco, México. Retrieved March 26, 2010 from http://cuentoenred.xoc.uam.mx.

| © Copyright rests with authors. Please cite TESL-EJ appropriately.

Editor’s Note: The HTML version contains no page numbers. Please use the PDF version of this article for citations. |