December 2011 – Volume 15, Number 3

Livemocha

| Title | Livemocha (http:/www.livemocha.com/) |

| Owner | Livemocha, Inc. |

| Creators | Shirish Nadkarni and Krishnan Seshadrinathan |

| Type of product | Social networking service |

| OS compatibility | Windows XP/Vista/7; Mac OS |

| Minimum hardware requirement |

Computer with Internet access |

| Target language | 38 languages |

| Price | Free access to Livemocha community & some basic language learning activities; Additional Premium Content via Gold Key Option available for $9.95 monthly subscription and $99.95 yearly subscription in 38 languages |

General Description

Livemocha, currently the world’s largest online language learning community, is a social networking service providing language learners the opportunity to communicate with native speakers (NSs) of numerous world languages while promoting cross-cultural learning and sharing. Created in response to the expensive language learning software currently on the market, Livemocha’s free web-based language learning social network gives learners a chance to connect with NSs of their target language (TL) by allowing participation in live chats, correspondence through asynchronous messaging and sharing feedback about learners’ production of the second language (L2). Additionally, the site offers basic language learning lessons, or “basic courses,” for free and “active courses,” for a monthly or yearly paid subscription. At present, the Livemocha community consists of over 12 million members from 195 countries and is growing by the hundreds daily.

Figure 1. Livemocha homepage

Registering for Livemocha and participating in the language learning community is free. After selecting from one of twelve language settings, users are prompted to select their native language and the language they wish to learn from a dropdown menu of 38 world languages. Users must identify their proficiency level in the L2, then specify their objective for learning the L2, the speed at which they want to learn and their preferred style of language learning. At this point, “connections” are immediately suggested and involvement in the social community begins.

Members stay in contact with their established connections and are contacted by other Livemocha members through their personal profile page. A learner uses the profile page as a way to make “friends” in the social network, read about other members’ activity, and receive recommendations based on her specified linguistic needs and learning preferences. A member may search others’ profiles to review their “teacher contribution scores,” a rating given by other learners based on the helpfulness of a member’s feedback, and “mocha points,” which are awarded to members by Livemocha based on the progress made in meeting personal language learning goals and the quantity of feedback given to other learners. The profile page is also a means by which members may initiate chat invitations with friends in their network, as well as monitor their own learning progress.

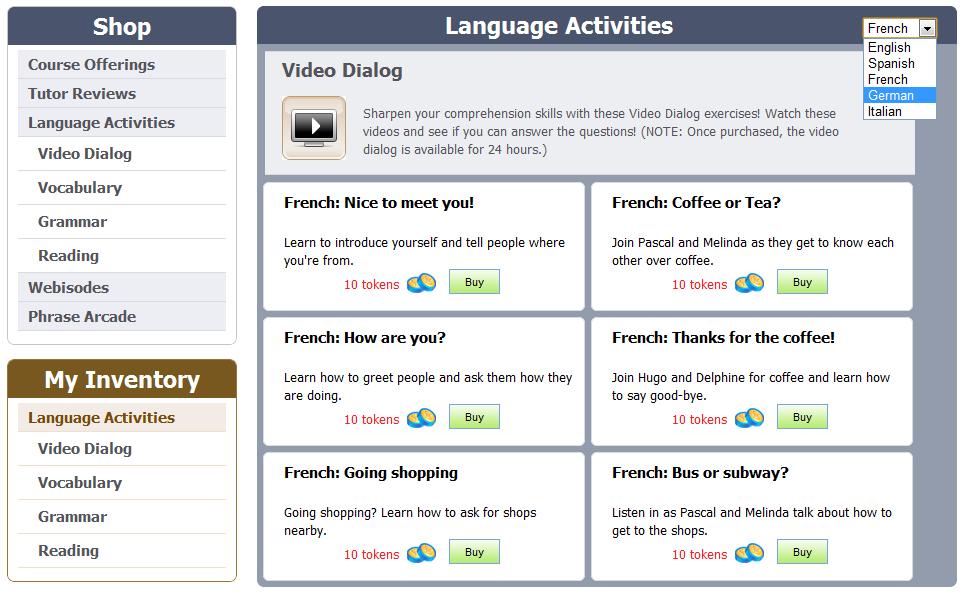

Livemocha members may also take part in “basic” and “active” language learning courses. The free “basic courses,” offered in 38 different languages, cater to beginning to intermediate-level learners and target writing, speaking and listening skills. These free online activities and lessons vary in quantity and quality based on the indicated TL and feedback from NSs of a less common TL may be slow or even unavailable, depending on members and their degree of involvement in the community. “Active courses,” available only in English, Spanish, Italian, French and German are intended for learners of varying proficiency levels (including advanced) and are available for purchase by monthly or yearly subscription. English language learners pay $39 a month and $199 a year while learners of the other “active course” languages pay $29 a month and $149 a year. The paid courses aim to build learners’ writing, reading, listening and speaking skills in the L2, and provide users with video and audio downloads, online phrasebooks and “expert reviews,” by NSs of the TL, guaranteed to arrive within 72 hours of exercise submission. “Active courses” also offer downloadable “certificates of completion” for each course completed.

Figure 2. Language activities available for purchase with tokens

Figure 2. Language activities available for purchase with tokens

Users may also purchase supplementary language learning activities, games and “expert tutor reviews” (each available in a limited number of languages) with tokens (80 tokens is equivalent to $1). Tokens can also be used to purchase video clips, language exercises, flashcard PDFs and, soon, mobile apps and travel phrasebooks.

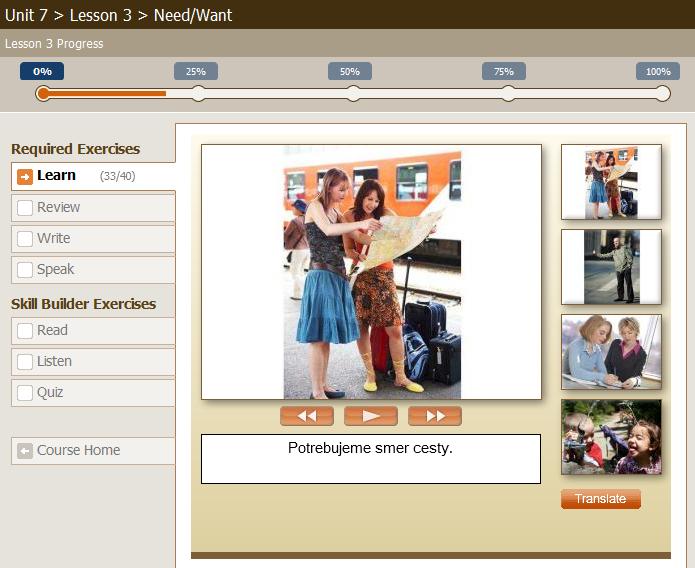

Livemocha’s language learning materials, developed in conjunction with partner publishing companies Harper Collins and Pearson Education, target a range of linguistic skills. Learning units are categorized by proficiency level and are divided into “required exercises” (engaging learners in listening, reading and writing in the L2) and “skill builder exercises” (involving reading and listening tasks). Exercises are followed by quizzes which assess learners’ comprehension of the instructed content.

Most skill development exercises employ the use of audio, video and written texts. For example, in vocabulary-building exercises, new words and phrases are presented with corresponding images, a feature that Livemocha creators claim “boosts retention” while allowing learners to hear NS pronunciation.

Figure 3. Screenshot of vocabulary lesson

Figure 3. Screenshot of vocabulary lesson

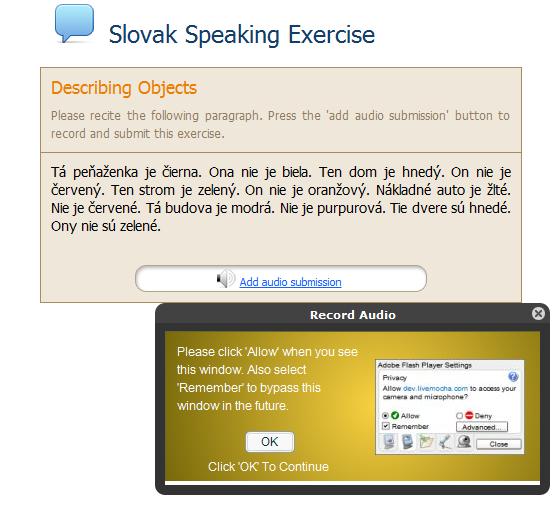

After completing speaking and writing exercises, a Livemocha member may upload the produced speech sample, which is then sent to NSs of the TL for review. For example, speaking exercises elicit production by asking a member to record herself reading a presented paragraph in the TL. The completed recording is sent to NSs who review the sample, comment on the learner’s “pronunciation” and “proficiency” via written and/or spoken feedback and make suggestions for improvement.

Figure 4. Prompt for speaking exercise

Figure 4. Prompt for speaking exercise

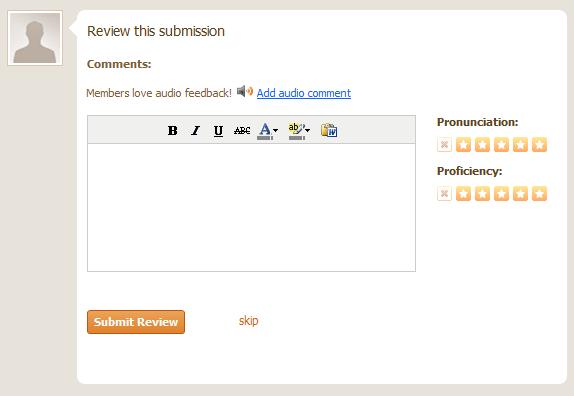

When a member has reviewed a NS’s feedback on her completed exercise, Livemocha sends her a similar exercise completed by a learner of her L1 for review. In this way, Livemocha members reciprocate others’ contributions to the language learning community via NS feedback exchange.

Evaluation

Livemocha’s slogan, “Creating a world in which every human being is fluent in multiple languages,” seems a claim only partially fulfilled by the combined efforts of community members and site resources. On the one hand, Livemocha successfully facilitates cross-cultural communication between members by promoting members’ participation in and establishment of an extensive, world-wide language learning community. Through the dynamism of social interaction, shared understanding and meaning emerge, as does one’s feeling of membership in a community of social practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991). The site provides language learners rare access to a community of native-speaking members of their TL, essentially positioning the NSs as private tutors who provide both synchronous and asynchronous feedback. The more the “social protocol” of receiving and giving feedback is repeated, the stronger the connections between community members become; what results is a “sense of community…capable of enhancing reciprocal relationships” and propelling members’ willingness to invest in and contribute to the group’s collective language learning goals (Daniel, et al., 2008, p. 7).

Figure 5. Format for providing feedback on a speaking exercise

Figure 5. Format for providing feedback on a speaking exercise

Also, because Livemocha is the largest language learning community online, it offers unique opportunities for members seeking to learn less commonly taught/learned languages. Though a limited number of language learning activities are available in some languages, Livemocha at least connects learners and NSs of less common world languages so they may participate in live chat or asynchronous message exchange.

Livemocha also holds numerous advantages for application in the classroom. Creators of Livemocha have tapped into a wildly popular resource for communication, social networking, and this online medium could be attractive for students learning in formal language learning settings. “Today’s teachers have to learn to communicate in the language and style of their students,” Prensky (2001) argues, and integrating social media into formal educational environments may encourage student involvement in language learning tasks and promote positive attitudes towards in-class and out-of-class learning (p. 4).

Yet another attractive feature of Livemocha is the control learners have over their own involvement in the learning process. Because lessons are self-paced, learners are able to control the speed at which they learn. Livemocha members may also participate in the learning community at their own convenience, wherever they have online access, and as much or as little as they want. Such control has been shown to reduce stress and anxiety sometimes associated with language learning (Warschauer, 1995).

Despite the potential benefits offered by Livemocha, multiple drawbacks must also be noted. Perhaps the most problematic of these drawbacks derives from the dubious claims made both explicitly and implicitly by Livemocha creators. The promise that members can “become fluent in just 20 minutes a day,” a guarantee also included in the Livemocha slogan, could be misleading for beginning language learners starting study in their L2 and experienced language learners discouraged by other programs, curricula or methods of language learning. Language learning is an involved and complex process that takes most learners years of study and practice before near-fluent levels can be attained. Guarantees that Livemocha will help a member achieve L2 fluency in “just 20 minutes a day” obscures the complicated and challenging language learning process.

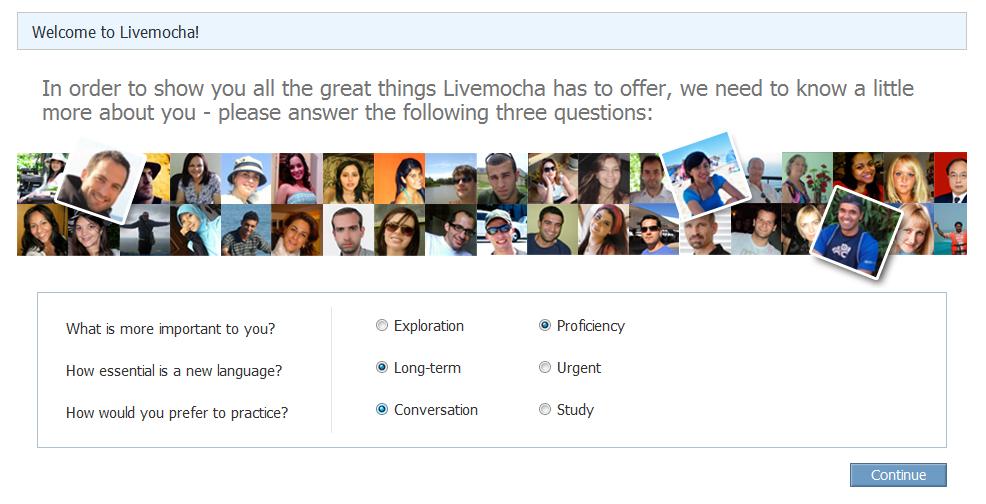

Figure 6. Welcome to Livemocha questionnaire

Figure 6. Welcome to Livemocha questionnaire

Another tenuous claim made by Livemocha creators implies that attainment of an L2 may be completed “urgently,” as can be implicitly understood from their “Welcome to Livemocha” questionnaire. These claims and promises can be deceiving to any level of language learner who may wish to become fluent quickly and easily, and may later serve as sources of great frustration when a learner’s expectations are not met.

In the same regard, members of Livemocha may be given a false sense of progress in language learning when their successes are reduced to “mocha points” or appear as filled in portions of a linguistic barometer, supposedly gauging the amount of the TL acquired. Because “mocha points” are awarded based on completion of Livemocha exercises and performance on post-exercise quizzes, and do not necessarily require learners to demonstrate their proficiency nor exhibit retention of the target linguistic knowledge, members may feel they are advancing in their L2 while their achievement may be relatively unsubstantiated.

Another confusing statement made by Livemocha creators is that language learners of all levels are welcome. While learners of any proficiency level may be “welcome” to join the community, beginning and lower intermediate level learners will undoubtedly struggle greatly with the content of the lessons. Exercises contain a large portion of written text and assessments are frequently only available in written form. A better means to scaffold beginners may be to integrate multiple media into both practice and evaluation activities, so as not to overwhelm learners of lower proficiency levels or dissuade them from participating in the community.

A subsequent shortcoming relates to the assistance offered to the learner. Livemocha alleges to offer support to the language learner, though this assistance is sometimes lacking. For example, the phrase translator, a tool provided with writing exercises, is able to retrieve words and phrases in a limited number of languages, thus making the translator irrelevant for those who do not speak the languages offered. Also, the translations it produces are sometimes inaccurate, which may lead the learner to use the words or phrases inappropriately in the future.

Figure 7. Phrase translator accompanying writing exercises

Figure 7. Phrase translator accompanying writing exercises

The assistance offered by members of the Livemocha community may also be problematic. Members who have indicated they are native speakers or are fluent in a language automatically receive the designation of “teacher” when giving feedback to learners studying that language. Yet, being a NS of a TL does not equate one’s status as a language teacher of that L1. NSs acquire their L1 in vastly different ways than those learning a L2, and often lack the metalanguage with which to talk about their L1. In other words, not all speakers providing linguistic feedback are equipped to handle grammar or usage-related questions pertinent to a member’s language inquiries, and the information they give may be inaccurate or misguiding. Additionally, the “teacher’s” feedback, provided in written or spoken form, is commonly given in their L1, and may be incomprehensible and, therefore, unhelpful to beginning level learners of the language.

Summary

Social media have become established fixtures in our communication landscape, and because “multilateral exchanges reflect the changing reality of language learning in a globalized world” (Lewis et al., 2011, p. 3), effective integration of media like Livemocha into the language learning process seems pertinent and timely. Though Livemocha may increase students’ motivation to learn their L2 through involvement in social networking and promote cross-cultural communication among community members with similar language learning objectives, teachers incorporating Livemocha activities into their classes and learners using the site on their own should exercise caution when interpreting Livemocha’s claims regarding “fluency.” A learner’s individual goals, as well as her current L2 proficiency, will ultimately help her determine if Livemocha is appropriate for meeting her language learning needs.

References

Daniel, B., McCalla, G., & Schwier, R. (2008). Social network analysis techniques: Implications for information and knowledge sharing in virtual learning communities. International Journal of Advanced Media and Communication, 2(1), 20-34.

Lave, J. & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis, T., Chanier, T., & Youngs, B. (2011). Mulilateral online exchanges for language and culture learning. Language Learning & Technology, 15(1), 3-9.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. On the Horizon. 9 (5), 1-6.

Warschauer, M. (1995). Virtual connections. Hawai’i: University of Hawai’i at Manoa, Second Language Teaching and Curriculum Centre.

About the Reviewer

Sarah Huffman is a PhD student in the Applied Linguistics and Technology program at Iowa State University. Her research interests include online academic writing instruction, uses for open source software in second language and systemic functional linguistic approaches to language development. She has developed online course materials for an ESL reading course at ISU and currently works as a teaching and research assistant for the English Department at Iowa State.

<shuffman iastate.edu>

iastate.edu>

| © Copyright rests with authors. Please cite TESL-EJ appropriately. |