March 2011—Volume 14, Number 4

Sharon Sharmini

Universiti Putra Malaysia, Malaysia

<Sharonsharmini83![]() yahoo.com>

yahoo.com>

Vijay Kumar

Universiti Putra Malaysia, Malaysia

<vijay![]() fbmk.upm.edu.my>

fbmk.upm.edu.my>

Abstract

Feedback plays an intervention role in the writing process. It is through feedback that writers are guided to achieve negotiated writing goals. Feedback encourages a process of discovery and this plays a developmental role in the writing process. In this paper, we report on three case studies that sought to understand cognitive processes when writers attended to feedback. Three ESL postgraduate students were asked to think aloud while attending to lecturer written feedback. Concurrent verbal protocols were analysed qualitatively using computer assisted data analysis software called Nvivo8. The findings from this study indicate that attending to written feedback is a recursive process. While recursively attending to feedback, the writers planned globally, locally, reflected, and justified. The findings suggest that dialogical type of feedback encourage recursiveness and planning. These are essential for the potential development of a writer.

Introduction and Literature Review

In this qualitative investigation, we report on three case studies drawn from a larger study which sought to understand cognitive process when writers engage with written feedback.

The process approach to teaching writing allows for intervention at any stage of the writing. Process writing emphasizes the recursive nature of writing. Within this process, which includes planning and considering an audience, feedback plays an important role as it has the potential to develop the writer’s skill and to orchestrate the text that is being generated. While writing is considered recursive, there is a paucity of literature that provides insight into the “recursiveness” of engaging with feedback. Studies on feedback have traditionally been done to identify the types of feedback that are deemed effective in the learning process. It has been recently reported that just like writing, attending to feedback is also a recursive process. In a study, utilising concurrent verbal protocols (Kumar, Kumar & Feryok, 2009), it was reported that students showed a tendency to move between text and idea generation in a back and forth type of movement. While this study shed light on the recursive nature of attending to feedback, it did not give any indication of the role of planning in attending to feedback.

Prominent models of writing such as those by Hayes and Flower’s (1980), Bereiter and Scardamalia’s (1987) Development Model and Hayes’s (1996) model emphasize the role of planning in the writing process. These models of writing suggest that planning does not take place only at the beginning of the writing task, but is a recursive process that can take place at any stage of the writing process. Studies on planning have shed light on how writers plan to generate ideas and to organise ideas. It is this planning that gives both a sense of direction and achievement to a writer. Skilled writers have also been acknowledged to plan extensively (Biggs, 1998). Given this understanding about the importance of planning in the writing process and the paucity in the literature on student engagement with written feedback, this study was done to gain further understanding on the thought process of writers when they attended to written feedback. This study sought to understand if planning, a component of the writing process, is similarly evident when writers engage with written feedback.

Methodology

Participants of this study were first asked to write on a prompt given. The three participants, Sameera, Rochelle, and Ain (pseudonyms), are ESL postgraduate students undertaking a course in composition theory and practice. As part of the course requirement, they were required to write an argumentative essay entitled: Success in Education is Influenced More by the Student’s Life and Training as A Child than by the Quality and Effectiveness of the Educational Programme. The three participants were selected based on the richness of verbalizations they were able to provide while attending to written feedback. No time limit was given to them and they wrote at their own convenience without any time or space constraints. When the participants handed in their essays, the lecturer provided written feedback on the drafts. Feedback was written on the margins of the text and also at the end of the text (see appendix 1 for a sample). The draft, with the feedback, was sealed in an envelope and returned to the students. They were asked to start thinking aloud and revising as soon as they opened the sealed envelope.

Findings

The participants of this study planned globally, locally, and also reflected when engaging with written feedback.

Global Planning in Feedback

The term global planning is generally understood as structuring a complete text. The following excerpt shows Sameera’s response to feedback:

LT: Provide a link into your argument. This paper puts forth an argument… (LT)

[LT- Lecturer Feedback]

TA: So in this particular part, this section, I am going to talk about family upbringing as well the effectiveness of education programme that I believe that they need to work hand-in-hand in a child’s development. (TA)

[TA- Think Aloud]

RD: In this paper, I put forth an argument that the success of the student’s life in their education is because of family upbringing as well the quality and effectiveness of the education program. (RD)

[RD- Revised Draft]

Similarly, Rochelle planned globally as she accepted the lecturer feedback. She made changes to the way she structured her essay which was evident in her revised draft.

LT: What is your stand? You’re beating around the bush. (LT)

TA: I’m going to sort of give a preview yaa… I, I remember you said that we need a preview sort of…

RD: I will conclude this essay by supporting my claims with evidence that student’s success is influenced by the student’s life that is family socioeconomic, education background and support provided by the parents. (RD)

Ain also planned globally. For instance,

LT: Preview your main points or argument. (LT)

TA: I need to do a lot of restructuring here. Okay…I need to find three strong arguments for the paper. Only three and then support it. (TA)

RD: In this paper, the three arguments that would be discussed to support this stand are (1) a child’s learning process starts from birth, (2) parents is necessary and important in early childhood education process and (3) childhood education are mostly influenced by informal education. (RD)

Local Planning in Feedback

Besides global planning, the writers in this study also planned locally. The term local planning is understood to be structuring at the paragraph level. In this case, Sameera was able to structure her paragraph in detail.

Provide research evidence to support your claim. (LT)

What is your main argument here? Always link to your stand in the paper. (LT)

I’m basically trying to say that the relationship that children have with their peers have linkage with their relationship that they have with their parents. Yes, I need to provide evidence to the claim. (TA)

When I have a point, have a topic sentence and elaboration and must always have articles to define and justify. (TA)

Sadly, patterns of association such as being accepted and rejected have been found as early as a toddler and in preschool years (Rah & Parke, 2007). Thus, the recognition of the importance of peer relationships to children’s social functioning has led researchers to question the origins of children’s social atatus among peers. (RD)

Followed by that, Rochelle also planned locally. She planned what should be written next in her draft. This planning encouraged Rochelle to make appropriate changes to her written draft.

Write your topic sentence and then provide the supporting details. (LT)

I’m sorry I, I guess I’m going to rephrase it and see how my topic sentence can can be put somewhere that I need Thank you giving me an example of a sentence that I think I can start with. (TA)

Child care is a major challenge for a child to pursue post secondary education with low-income parents (Kappner, 2002). (FD)

[FD- First Draft]

Socioeconomic background influences the quality of education a student receives. (RD)

It should be recalled that Ain also planned when she accepted feedback. She also planned locally and knew what should be included next in her written draft. The following excerpt shows Ain’s response to feedback that encouraged her to make changes in her paragraph by using the appropriate signposting.

Can you tell me your main point in this paragraph is? You say home environment is more important but keep discussing about institutions. (LT)

I’m really confused. Hhmm…meaning I didn’t state my main point here. That’s my mistake. (TA)

So, I think what I can do here to improve my arguments is follow his structure where I state my stand and then I give arguments of my stand and in the same paragraph. Also, include signposting. (TA)

Despite the planned curriculum by the Ministry, I believe that success in education is influenced more by the student’s life and training as a child. (FD)

Firstly, I believe that success in education is influenced more by the student’s life and training as a child because a child’s education or learning process starts right from birth. (RD)

Recursiveness in Planning

While planning, writers in this study reflected and also thought about how they could provide justification for what they wrote. This seems to indicate a recursive step. In the excerpt below Sameera, for instance, planned, followed by reflecting on the need to search for articles in order to support her statement, and lastly, provided justification for her argument.

Ok, now I am going to talk about socioeconomic and I need one paragraph [planning]. Ok I need articles that support my statement [reflecting] and the one I have is Coleman’s Report where he talks about family income affecting the child’s learning [justifying]. (TA)

There were instances of Rochelle reflecting on the lecturer feedback and justifying herself by accepting her mistake. The lecturer feedback encouraged Rochelle to plan by rephrasing the sentences and to provide empirical evidence to support her argument.

Well I think I’m I’m jumping into some something else [reflecting]. I guess it is not worded rightfully aaa…yaa…when I said most studies yaa… I admit the fact that I have to get some reference if not it would be something that I plucked out from [planning]. I am going to rephrase it and I’m going to [justifying]. (TA)

Ain also reflected on the lecturer feedback. The feedback helped Ain to construct a proper academic paragraph. Ain explained what she was going to do in order to achieve her writing goals in this assignment.

I think the main thing I need to do is to restructure my essay because here he mentioned about restructuring my arguments [reflecting]…I structure my arguments and provide the supporting details [planning]. So, what I should do is follow his structure where I state my stand and then I give arguments of my stand and in the same paragraph, let say paragraph one, I give my argument…I refute some ideas on this issue [planning]. Maybe…I…I…I should…I…maybe that is the best way …for me to refute [justifying]. (TA)

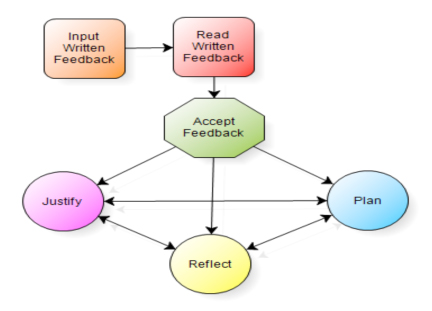

Clearly, these case studies shows that the writers planned, justified, and reflected when they accepted the lecturer feedback. It is interesting to note that the writers moved back and forth between these processes during their acceptance of the feedback. This clearly indicates that attending to feedback is a recursive process. This can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Attending to Feedback

Discussion

The thought processes of the participants seem to indicate that they moved between different stages of writing when they attended to lecturer feedback. The constant movement between the text, written feedback, and generating ideas by way of both global and local planning, reflecting and justifying, indicate that the writers were attending to feedback recursively. The data from this study clearly indicates and supports an earlier study (Kumar, Kumar & Feryok, 2009) that found attending to feedback is a recursive process.

However, the present study indicates that one main feature that is attributed to recursiveness is planning. The maxim to plan is to think before acting (Hayes & Nash, 1996). The writers in this study recursively moved back and forth from lecturer feedback and written text because they were thinking of what to do next. Planning is viewed as leading to a sequence of steps that are taken in order to achieve a specific goal (Hayes & Nash, 1996). These steps are non-linear. An example taken from Sameera’s TAP (Think Aloud Protocol) is: “Next sub point is social relationship where I will be talking about peers. Ok I need articles that support my statement… Sameera was planning what to do in order to ensure that her writing was argumentative in nature. She had a specific, clear goal to achieve.

It is important to know how writers in this study engaged themselves in planning. An influential model of writing by Hayes and Flower (1980) emphasizes the importance of planning. The planning process in this model involves a writer generating ideas from long−term memory and the task environment and these ideas help the writer to decide what to write and how to write in the planning process. It will be recalled that the long-term memory stores knowledge of topic, audience, and writing plans, whereas the task environment composes rhetorical problems (topic, audience, and motivating cues) and the emerging text itself (text produced so far). However, the writers in this study were able to generate new ideas from the lecturer feedback and did not rely completely on long term memory and task environment. As an example, lecturer feedback helped Rochelle to realise her mistake. As Rochelle read the feedback, “When you use ‘although’ compare ideas-not names and separate issues (TAP)” she realised her mistake and said: “Ya, I believe so after you point it out. I realised that by putting although I am not referring to someone else earlier because there is no comparison why should i use although (TAP).” In her revised draft Rochelle provided relevant ideas that were supported by empirical evidence. Thus, she did not generate her idea from long-term memory or from the task environment. She was able to decide what to write on and envision her thoughts and goals based on the lecturer feedback.

Sameera, for instance, displays how writers attended to feedback recursively by planning. She constantly moved back and forth from the lecturer feedback while revising. When she accepted feedback, she revised her feedback by planning. For instance, “When I have a point, I must have a topic sentence, elaboration and details and must always have articles to define and justify (TAP).” Planning her written task encouraged Sameera to refer to the lecturer’s feedback and text repeatedly. This movement prompted Sameera to draw a mind map while planning. Hayes & Nash (1996) claim that in the writing process, planning is a cognitive activity but the result of planning involves mental construct, physical artefact, or a blend of both. For example, planning in the game of chess involves mental construction where the player stores his plan in his memory; in design, by comparison, planning involves physical artefacts where heavy use is made of sketches drawn on paper. In this study Sameera not only used her mental construct to plan but she also used physical artefact. She drew a mind map to help her clarify the structure and the flow of her argument. Therefore, Sameera was able to envision her writing goals through the suggestions and feedback that was provided by the lecturer. The process of reading and reviewing the lecturer’s feedback and text repeatedly led Sameera to plan her written text better.

Similarly, the repeated movements between lecturer feedback and text helped the writers in this study to identify and address issues that were highlighted by the lecturer. They were able to analyse their own written drafts. An example is provided from Ain’s TAP as she read the lecturer feedback: “What is your argument? What you are writing doesn’t seem to be related to your stand?” This feedback encouraged Ain to reflect and analyse her own written text. She responded by saying “I think what I can do here to improve my arguments is to follow the structure where I state my stand and then I give arguments of my stand in the same paragraph (TAP).” Ain was able to improve her written text by planning the changes and then correcting on her own. This indicates that the lecturer feedback induced the writers to monitor themselves while attending to their feedback (Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006).

Thus, it can be clearly seen that lecturer feedback encouraged the writers to plan. They were able to distinguish their goals and make their own judgements about what to write. Hayes & Nash (1996) point out that the act of planning is similar to “sculptures that create images in stone but plan them in clay” (p. 31). In this study, lecturer feedback was the clay that helped the writers sculpt their written text.

Implications

The findings from this study give a clear indication that engagement with written feedback is not only recursive but also involves planning. What seems to be apparent is that feedback that is provided needs to be dialogical in nature so that these processes can be invoked. An analysis of the types of feedback that were given indicates that statements, imperatives, and questions comments (feedback) seem to be very helpful in the revision process (Ferris, 1997). Statement comments indicate information that it is expected the writers will act upon (Ferris, Pezone, Tade & Tinti, 1997). For instance, the lecturer commented ‘Too many generalized statement which are true to a certain extend but you must provide empirical evidence to support all the claims.’ In the revised draft, the writer provided empirical evidence of their response to this form of feedback. For instance, the sentence was revised to: ‘Family factors such as family income, size and parents’ education are socioeconomic status that affects the child’s learning (Coleman, 1996; Greenwood & Hickman, 1991).’ This form of feedback gives a clear direction to the writers on how to respond to the comments because the writers were directly asked or told to do something. It seems, in this study, lecturer comments were useful to the writers. The writers were not confused but were able to understand the meaning of the comments. However, they also knew how to use them productively in order to improve their drafts.

Besides this, question comments helped the writers to think critically. This encouraged them to be more careful as they revised. For instance, one participant received the feedback question, ‘What is your main argument here? Always link to your stand in the paper.’ In the initial draft, the writer had written ‘I believe the influence of a child success is education from life rather than academic.’ After considering the lecturer’s feedback, the writer revised and reconstructed her sentence by agreeing to the feedback provided by the lecturer. Thus she wrote ‘Apart from the two factors, another argument that could support the idea that children’s successful education is influenced more by the student’s life and training.’ This form of feedback encourages the writers to revise carefully by stimulating them to provide relevant information to the text. This optimises self-regulated learning (Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006). Self-regulated learning seems to take place when a writer receives feedback on a draft from the lecturer, and he/she is expected to revise and make the relevant amendments based on the written feedback that was provided. It should be noted that feedback offers a sense of direction to the writer (Hyland & Hyland, 2006).

Lastly, imperative comments are basically suggestions. For instance, ‘Perhaps you could summarize and all these under conducive home environment.’ In the initial draft, the writer wrote ‘family involvement’ but in her revised draft she wrote ‘conducive environment.’ Evidently, the writer accepted the lecturer’s suggestion. A tentative explanation is that such comment encourages the writers to develop and generate new ideas. Apparently, lecturer feedback acts as a channel of opportunity to enhance the writers’ writing through the revision process (Hyland & Hyland, 2006).

The most important goal of feedback is to provide information to the writer. In order to achieve this goal, the first thing to bear in mind when writing a comment is clarity. The lecturer in this study provided feedback that encouraged the writers to pay a great deal of attention to follow the instructions and revise the drafts. Interestingly, certain types of comment did appear to lead to more effective revision than other types (Ferris, 1997, 2002, 2003). This result seems to contradict the conclusion of Hillocks (1986) that “lecturer comment has little impact on student writing” (p. 167). The writers in this study had a positive impact from the lecturer feedback. It can be concluded that lecturer’s written feedback has a great effect on student writing and also on their attitude toward writing (Leki, 1990).

Note

A version of this paper was presented at the 14th English in South East Asia Conference in Manila, 26-28 November 2009.

About the Authors

Sharon Sharmini is a masters student in applied linguistics. Her research interests are in the areas of feedback practices and academic writing. She also teaches courses in academic writing and public speaking.

Vijay Kumar is a senior lecturer with the Department of English in Universiti Putra Malaysia. He has more than 25 years of teaching experience. He earned his doctorate in Applied Linguistics from the University of Otago, New Zealand. His research interests are in academic writing, feedback practices and postgraduate development. He is an invited member of the International Doctoral Education Research Network.

References

Biggs, J. (1998). Student approaches to essay-writing and the quality of the written product. Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong. [ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 293 145].

Ferris, D. R. (1997). The influences of teacher commentary on student revision. TESOL Quarterly, 31(2), 315-339.

Ferris, D. R. (2002). Treament of error in second language student writing. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Ferris, D. R. (2003). Response to student writing: Implications for second language students. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Ferris, D. R., Pezone, S., R.Tade, C., & Tinti, S. (1997). Teacher commentary on student Writing: Description & Implication. Journal of Second Language Writing, 6(2).

Hayes, & Nash (1996). On the nature of planning, In C. M. Levy & S. Ransdell (Eds.), The Science of Writing: Theories, Methods, Individual Differences and Application, (pp. 57 – 71. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hillocks, G. (1986). Research on written composition: New directions for teaching. Urbana, IL: ERIC Clearinghouse on Reading and Communication Skills and the National Conference on Research in English

Hyland, K. & Hyland, F. (2006). Feedback on second language students’ writing. Language Teaching Research, 39, 83-101.

Kumar, M., Kumar, V., & Feryok, A. (2009). Recursiveness in written feedback. New Zealand Studies in Applied Linguistics, 15(1), 26-37.

Leki, I. (1990). Coaching from the margins: Issues in written response, In B.Kroll (Ed.), Second Language Writing, (pp. 57-68). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Nicol, D. J., & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self- regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 31(2), 199-218.

Appendix

| © Copyright rests with authors. Please cite TESL-EJ appropriately.

Editor’s Note: The HTML version contains no page numbers. Please use the PDF version of this article for citations. |