September 2009 – Volume 13, Number 2

EnglishAddicts.Com

| Title | English Addicts (http://www.englishaddicts.com) |

| Publisher | Edulang |

| Contact Information | http://www.edulang.com/ Tel. +33 (0) 298634200 Fax +33 (0) 298634757 Address: Rue Yves Guyader, 29600 Morlaix, France |

| Type of product | Website for listening comprehension practice |

| Platform | Web |

| Minimum hardware requirement |

A computer with broadband Internet access, a browser, and speakers (or headphones). 1024 X 768 screen resolution |

| Windows Media Player or QuickTime Player | None needed |

| Price | Free account for the latest lesson and for keeping personal scores Full access to all lessons for 1 year: € 120 |

Overview

Listening ability in first language (L1) acquisition develops with receptive, constructive, and interpretive aspects of cognition interdependently, and this skill receives less attention in L1 education, while in second language (L2) development, direct intervention may be more effective since most learners acquire L2 after cognitive processing skills and habits in the L1 have been established (Rost, 2005). Nonetheless, listening is considered not only a skill area in L2 performance, but also a primary means of acquiring the target language (Feyten, 1991; Biemiller, 2003; Rost, 2005).

Rost (2005) proposed three basic processing phases that are simultaneous and parallel in L2 listening. The three processes and their sub-processes are: (1) decoding: attention, speech perception, word recognition, and syntactic parsing; (2) comprehension: identifying salient information, activating appropriate schemata, inferencing, and updating representations; (3) interpretation: comparison of meanings with prior expectations, activating participation frames, and evaluation of discourse meanings. In the early 1980s, the burgeoning field of second language acquisition (SLA) was dominated by the concept of the input hypothesis and the view that comprehensible input is all that is needed to acquire a language (Krashen, 1981). Rost (2007), however, claimed that presentation of input alone is not enough. “We also have to plan interventions that develop their skill at making the input comprehensible” (p. 104). He emphasized that the core of the input hypothesis was to make instructional intervention successful, which leads learners to want to make the input comprehensible. Thus, he suggested that interventions can be helpful in enhancing listening skill, and they are “those that promote the listener’s motivation by advancing the listener’s goals for listening” (p. 104).

Based on Rost’s analysis, an ESL/EFL learning website that stresses listening skill should both recognize and facilitate listening processes and provide learners with helpful interventions. Chapelle (1998) reviewed seven hypotheses and their empirical and/or theoretical bases that are relevant for developing multimedia computer-assisted language learning (CALL) and suggested criteria for the development, which are (1) making key linguistic characteristics salient, (2) offering modifications of linguistic input, (3) providing opportunities for “comprehensible output,” (4) providing opportunities for learners to notice their errors, (5) providing opportunities for learners to correct their linguistic output, (6) supporting modified interaction between the learner and the computer, and (7) acting as a participant in L2 tasks. Yang and Chan (2008) further developed a set of evaluation criteria for English learning websites. Four of the 46 criteria items that they established were directly related to listening: (1) The content of the listening comprehension is in an authentic context. (2) In listening comprehension, the speech intonation is contextually appropriate to the specific area that the website developer is from. (3) In listening comprehension, the pronunciation is recognized by most English speakers in the specific area that the website developer is from. (4) Multimedia-aided listening materials are provided. These concepts were integrated to form an evaluation framework for reviewing language learning websites focused on listening comprehension. This paper applies this framework to evaluate English Addicts.

Features of Edulang’s English Addicts

English Addicts is a daily web service that focuses on improving learners’ ability to listen to and comprehend international English. In the product brief on the website, it emphasizes that 75% of exchanges in English take place between non-natives; thus in the lessons, English Addicts provides audio news reports with a variety of accents to help users understand international English.

English Addicts provides a new daily lesson from Monday to Friday, from the end of September to the end of June (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The home page and menu of English Addicts

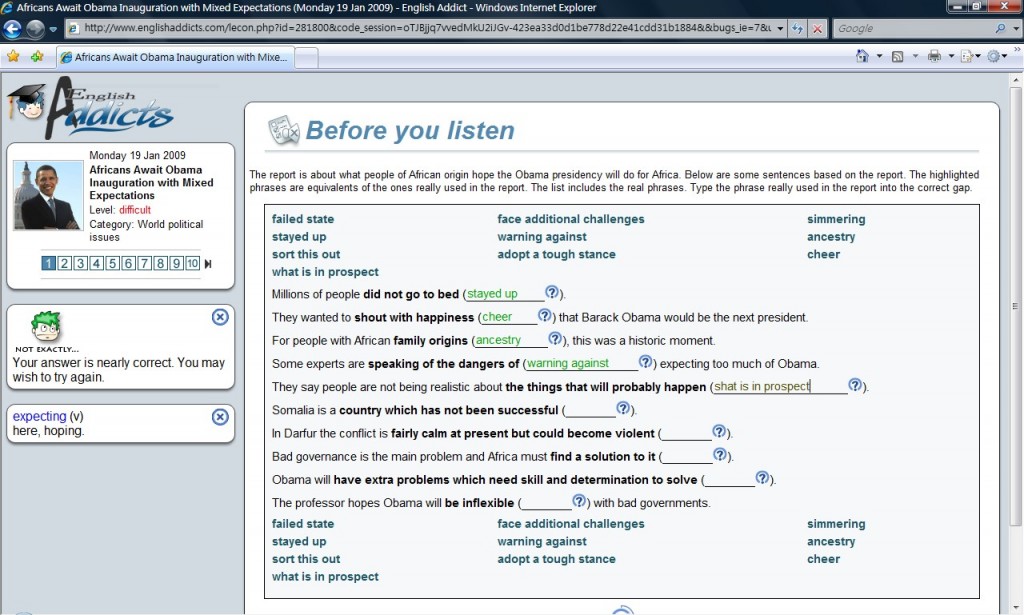

In every lesson, there is an audio news report (approximately 2 to 4 minutes) for the users to listen to online and/or download to their computer, and information about the report. The lessons are structured into 10 activities that start with before listening activities (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Exercise 1—“Before you listen”

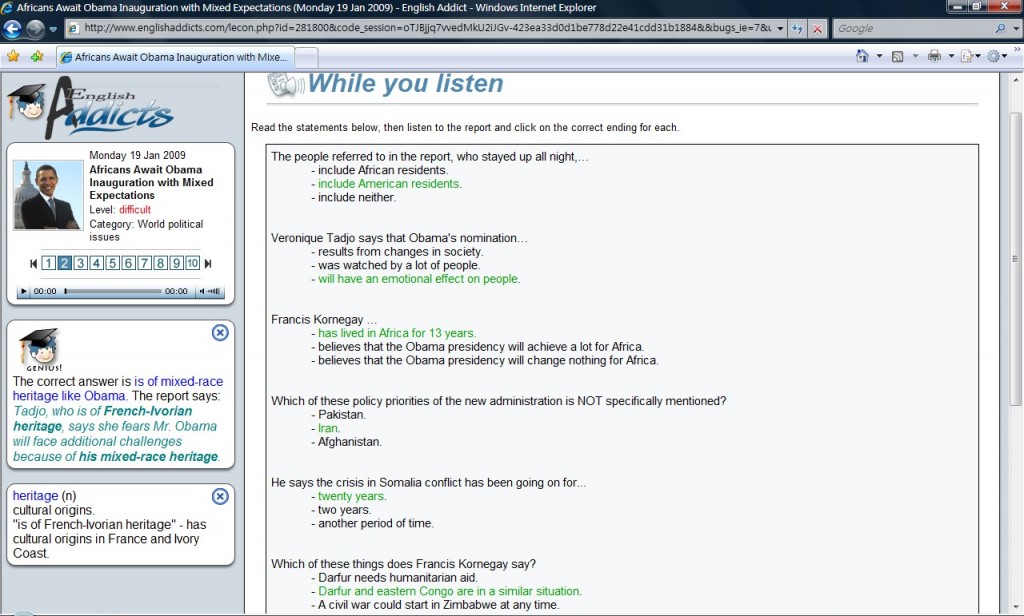

Next, lessons continue with while listening exercises (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Exercise 2—“While you listen”

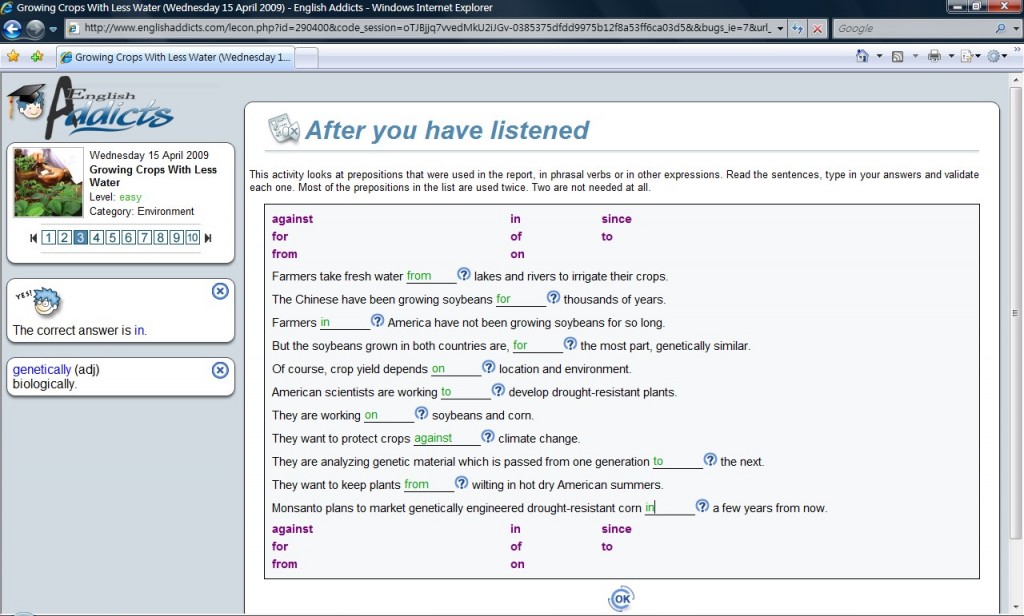

Activities continue with after listening exercises (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Exercise 3—“After you have listened”

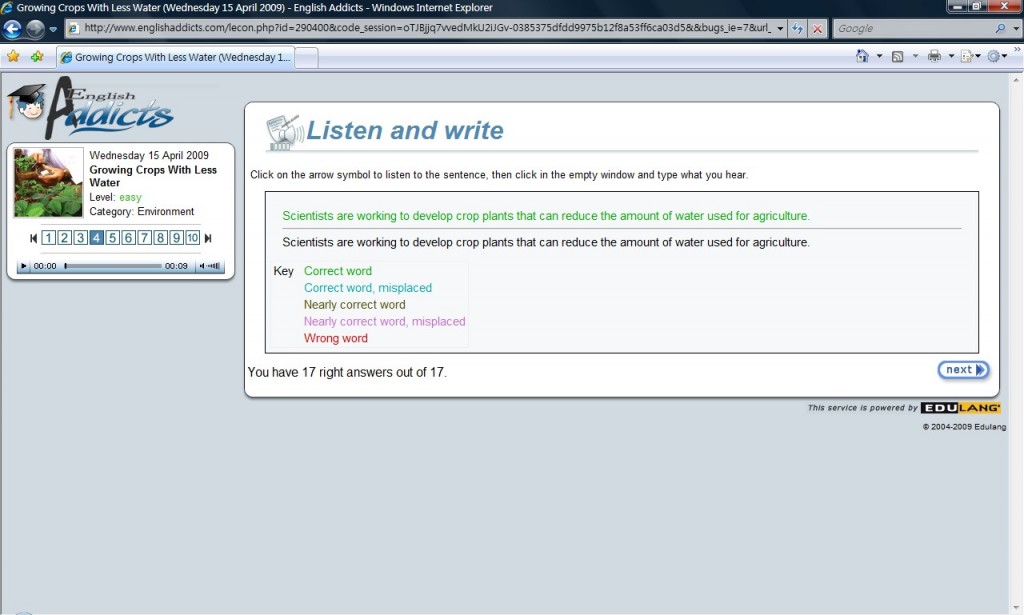

Finally, there are also dictations and other activities (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Exercises—“Dictation” and answers

Every lesson provides a new topic and glossary intended to allow learners to practice for 10 to 20 minutes every day and to prevent them from being overwhelmed by too much information when starting a lesson.

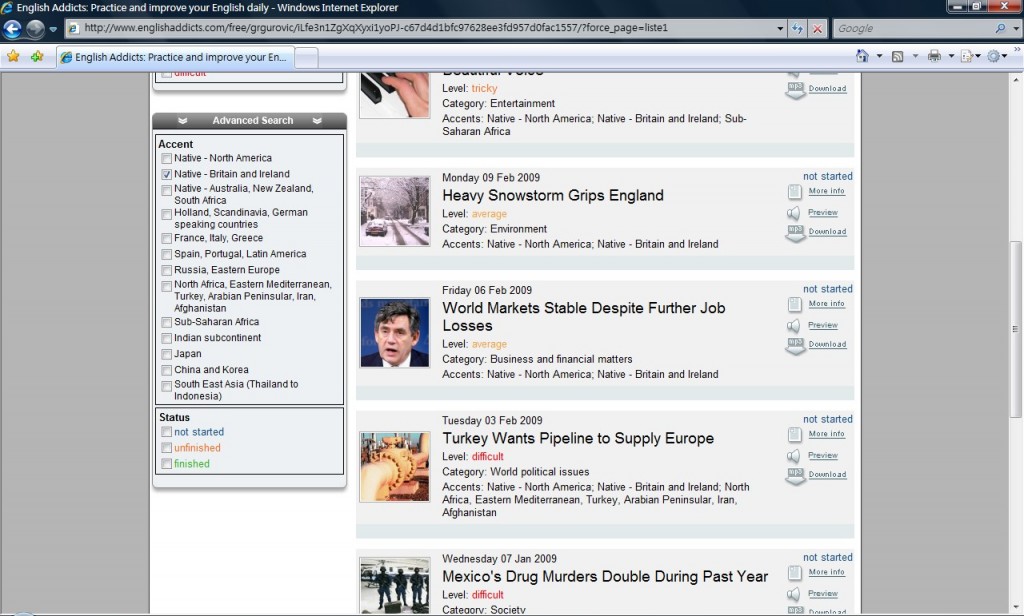

There are more than 1,000 lessons on the website of English Addicts, and subscribers are eligible to review past lessons. The lessons are organized into 7 categories based on the topic, 4 levels based on difficulty. How these categories are presented can be seen on the left side of the screenshot in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Lesson organization menus

Lessons are also sorted into 13 major accent categories based on the dialect of the speaker (see left side of Figure 7).

Figure 7. Advanced search for “Accents”

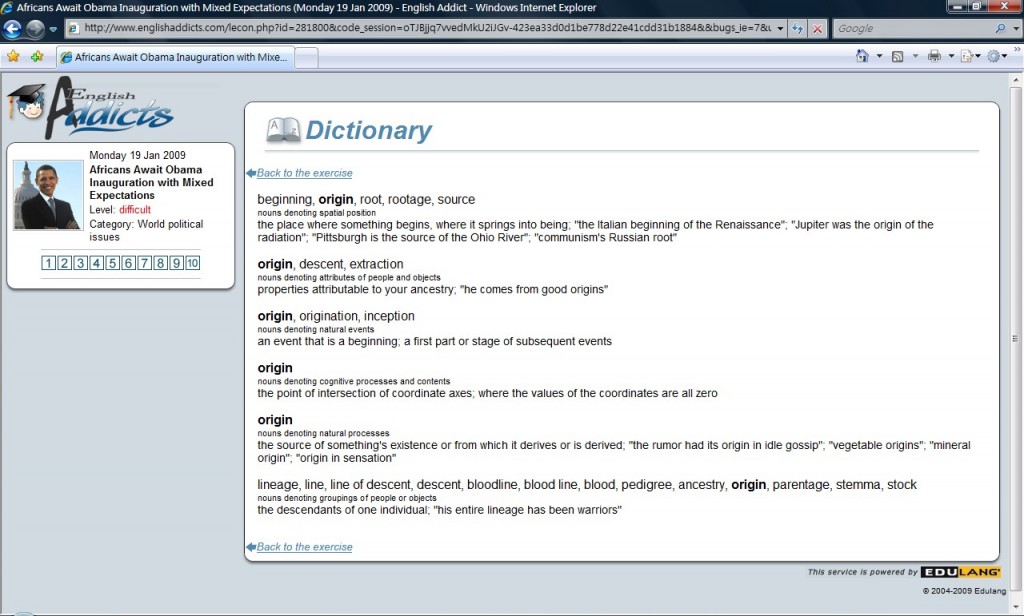

Using these tools, learners can search for lessons which meet the particular criteria they set. Once in the lessons, users can right-click a word in the activities to consult the online dictionary (see Figure 8).

Figure 8. Handy dictionary

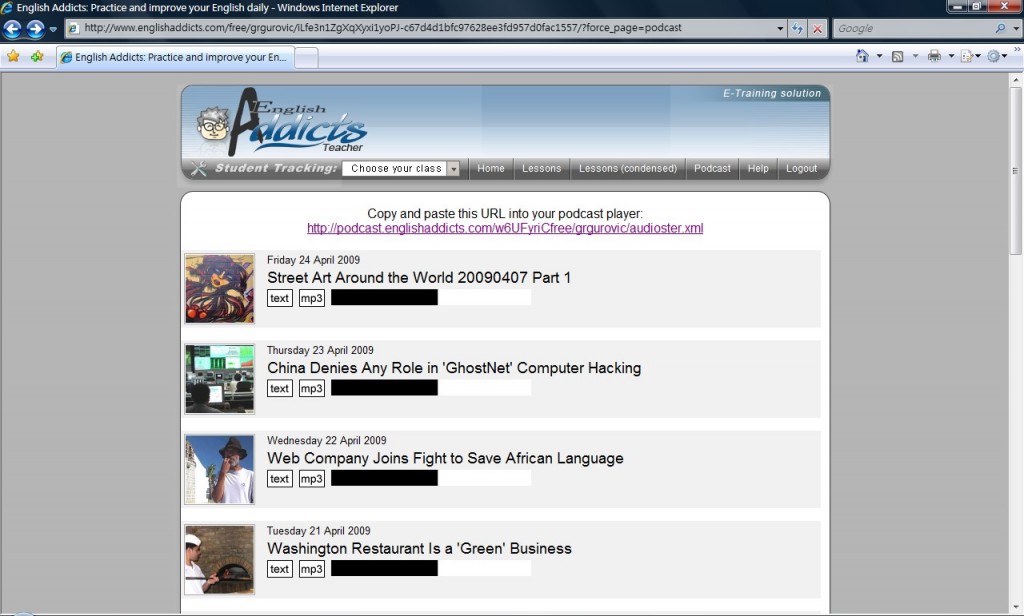

For each exercise activity, the software corrects users’ errors, and reports their score. In addition to using a computer to access the materials, English Addicts allows users to download recordings to be played as a podcast, which highlights the mobility of technology-enhanced language instruction (see Figure 9).

Figure 9. Mobile function—“Podcast”

Evaluating English Addicts in listening comprehension and English learning

In order to evaluate English Addicts, it is important to assess how well it helps motivate learners and improve their listening skills. This review is based on seven criteria chosen and/or incorporated from the literature described above. Although the list does not include all aspects of English learning and CALL principles described above, the chosen criteria can serve as a reflection of how CALL can assist English learners’ listening comprehension.

Evaluation

1. Make key linguistic characteristics salient.

In the lessons of English Addicts, the first activity (i.e., “Before Listening”) facilitates word recognition in the decoding process. It also helps with identifying salient information and activating appropriate schemata in the comprehension process. Filling in blanks in context with the help of wordsquares, definitions, and hints help the learner recognize key vocabulary and its usage before listening to the relevant audio news report. As Rost (2005) put it, “the activation of background knowledge (content schemata and cultural schemata) that is needed for comprehension of speech are linked to and launched by word recognition” (p. 508). This activity can facilitate perception of the audio input. Thus, it meets the first criterion.

2. Offer modifications of linguistic input.

In the “While Listening” portion of lessons, English Addicts provides the user with control of playing and replaying the audio news report with a timer indication. It does not, however, provide the learner with control of the speed, which would also be useful. Although this can be done by downloading the audio report and editing it with computer software, the user cannot modify the speed of linguistic input on the webpage itself. This kind of modification, as Chapelle (1998, p. 27) stressed, is distinct from the “authentic” materials found on the Internet because they hold the potential to provide the learner with comprehensible input rather than just input. The wide variety of international accents of the reporters in different lessons and topics with different levels of difficulty, however, does offer some modifications of audio input in a larger sense.

3. Provide opportunities for learners to notice their errors.

In every lesson, nine activities, including pre-listening and post-listening gap-filling exercises, multiple-choice questions while listening, dictation exercises, and text transcription, all provide opportunities for learners to notice and correct their errors with immediate prompts and/or answers. This is a strength of English Addicts because it not only helps learners notice their errors, but it also offers explanations and definitions of the correct answers. One way to improve this feature would be to provide pronunciation guidance via audio clips or at least phonetic renderings of the words, since, after all, the intended focus of the lessons is listening ability.

4. Support modified interaction between the learner and the computer.

To a small extent, the lessons support modified interaction between the learner and the computer with prompts and unlimited opportunities to find the correct answer. These interactions help move the learner toward a task goal and focus on the language (Chapelle, 1998). However, the “task” is not clearly specified on the website and needs further integration with other classroom tasks or other Internet resources such as an “audioblog for engaged listening” (Healey, 2007). As Bernard Susser and Thomas N. Robb (2004) stated, learners create their own learning strategies based on the interaction possibilities available in the software, and do not always use software in the ways the designers intend.

5. Provide the content in an authentic context.

The lessons of English Addicts are based on real-life news reports; thus the text and audio content of the listening is provided in an authentic context.

6. Make the intonation contextually appropriate to the specific area and the pronunciation recognized by most English speakers in that area.

This is a real strength of English Addicts. The over 1,000 news reports are by reporters with 13 different types of accents, including 3 native accents and 10 international English accents. As the product brief emphasizes, one of the major goals of English Addicts is to make you understand the people you speak with, regardless of their accents. In the lessons, the intonation, accent, and pronunciation are contextually appropriate and can be recognized by most English speakers in the specific areas.

7. Provide learners with multimedia-aided listening materials.

This is a potential weakness of English Addicts. Although the audio contents are news-based, the lessons could have included visual aids (e.g., more news photos, flash, or videos) that are related to the content in addition to the one daily photo displayed beside the topic. Even if the publisher wishes to help learners focus on listening comprehension without interruption, multimedia aids can still be integrated into activities other than “while listening” in order to motivate and attract learners, as well as activate the learner’s prior knowledge.

Conclusions

English Addicts, as a Web service for English learning focusing on listening comprehension, has strengths and weakness. In addition to those listed above, strengths include:

- Game-like activities, such as wordsquare, and interesting hints and feedback.

- Abundant topics that cover a wide variety of issues in the world.

- Four levels of difficulty (including the “tricky” level) that allow the learners to experience and examine their listening comprehension proficiency.

- Individual score reports help learners trace their learning progress.

- The keyword search function not only facilitates targeting certain topics, but also is a useful tool for organizing a greater collaborative language learning task. It can be integrated into a curriculum that involves English listening, speaking, reading, and writing.

- The “Help” function on the website describes the activities of the lesson, and it is helpful to learners who are less familiar with using instructional technologies.

- The look and interface of the website are clear and user-friendly.

- The “Podcast” function successfully incorporates mobile technology with language learning.

On the other hand, improvements could include:

- Increasing multimedia aids to motivate and facilitate learning.

- Designing a task for each lesson that would encourage human-to-human interaction and collaboration.

- Adding pronunciation guidance to the dictionary.

- Adding contents from other authentic contexts, for example, real-life conversation, academic speeches, etc.

- Providing more content in a lesson. The publisher’s expectation of 10 to 20 minutes’ daily learning may not be sufficient for English learners to make significant progress in listening comprehension, though it may be appropriate for people who do not have much time to learn.

Learners should:

- Take as much time as possible in listening to the audio content.

- Create their own strategy of learning using this website (e.g., repetition, using it as a tool for a larger task, etc.), depending on the availability of resources and on their own needs.

References

Biemiller, A. (2003). Vocabulary: Needed if more children are to read well. Reading Psychology, 24 (3-4), 323-335.

Chapelle, C. (1998). Multimedia CALL: Lessons to be learned from research on instructed SLA. Language Learning & Technology. 2(1), 21-39.

Feyten, C. M. (1991). The power of listening ability: An overlooked dimension in language acquisition. The Modern Language Journal, 75(ii), 173-80.

Healey, D. (2007). Classroom practice: Language knowledge and skills acquisition. In J. Egbert & E. Hanson-Smith (Eds.), CALL environments: Research, practice, and critical issues, (2nd ed., pp. 173-192). Alexandria, VA: Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages.

Krashen, S. (1981). Second language acquisition and second language learning. London: Pergamon. Retrieved June 18, 2009, from http://www.sdkrashen.com/SL_Acquisition_and_Learning/

Rost, M. (2005). L2 listening. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning, (pp. 503-527). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Rost, M. (2007). Commentary: I’m only trying to help: a role for interventions in teaching listening. Language Learning & Technology, 11(1), 102-108.

Susser, B., & Robb, T. N. (2004). Evaluation of ESL/EFL instructional websites. In S. Fotos & C. M. Browne (Eds.), New perspectives on CALL for second language classrooms, (pp. 279-296). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Yang, Y. C., & Chan, C. (2008). Comprehensive evaluation criteria for English learning websites using expert validity surveys. Computers & Education, 51, 403-422.

About the Reviewer

Jia-Shian Su is a PhD student in Language and Literacy at Washington State University. He has twelve years of EFL and ten years of computer-related teaching experience at colleges and universities in Taiwan. His research interests are in CALL and TESL. He has published several articles in journals in Taiwan and in the U.S.A. such as ChienKuo Journal and CALICO. >raphaelsu hotmail.com>

hotmail.com>

|

© Copyright rests with authors. Please cite TESL-EJ appropriately. |