June 2010 – Volume 14, Number 1

Active Reading

| Title | Active Reading |

| Publisher | Clarity Language Consultants, Ltd.

Hong Kong office

UK office

|

| Type of product | CD or online software for developing reading skills |

| Platform | Windows standalone, network, online, Mac online. |

| Minimum hardware/software requirements |

CD version: Windows XP, Vista, 7.0

Online version: Internet Explorer 7, Firefox 2, or Safari 3 |

| Price | 1 computer license: US $270; 20 licenses: US $1,340 |

| Supplementary software |

V.9 or higher Adobe Flash Player. |

Introduction and criteria for program evaluation

The task of finding high quality language learning materials has become difficult for teachers because of the large array of software that is available nowadays. In addition, how to use technology effectively for learning has been an issue for many years. Bransford, Brown & Cocking (2000) note that “Inappropriate uses of technology can hinder learning— for example, if students spend most of their time picking fonts and colors for multimedia reports instead of planning, writing, and revising their ideas” (p. 206). On the other hand, Judge, Puckett, and Bell (2006) note that “Most educators agree that computer access and literacy have become vital and necessary for young learners in the 21st century” (p. 52). Similarly, Lovell and Phillips (2009) suggest that technology can be an important aid to classroom work in literacy instruction because the technology can “enable students to enjoy immediate individual feedback, work independently, and gain a sense of accomplishment” (p. 201). Other potential benefits of using technology for learning are that “Students can work with visualization and modeling software that is similar to the tools in nonschool environments, increasing their understanding and the likelihood of transfer from school to nonschool settings” (Bransford, Brown & Cocking, 2000, p. 207).

Despite all these potential benefits, technology can only be a good choice if teachers have sufficient background knowledge of and skill with the programs they want to use. Choosing in which programs to invest time and effort, however, is complicated because it is not an easy process to evaluate a web site or software. Finding time to perform an evaluation can be a challenge, and even when time is available, the software or the web site must be evaluated using useful criteria. One good example of criteria that can be used to evaluate technology is provided by Cummins, Brown & Sayers (2007). Their six criteria will be used to evaluate the Active Reading program, the focus of this review. These design principles for technology-supported instruction are that it should:

- provide cognitive challenges and opportunities for deep processing of meaning;

- relate instruction to prior knowledge and experiences;

- promote active self-regulated collaborative inquiry;

- promote affective involvement and identity investment;

- encourage extensive engaged reading and writing; and

- develop learners’ strategies for effective reading, writing, and learning (p. 109-110).

General program description

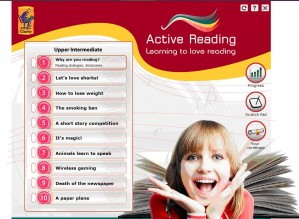

Active Reading is designed to help English as a foreign language (EFL) and English as second language (ESL) teachers and students alike. This software has six levels: elementary; pre-intermediate; intermediate; upper-intermediate; pre-advanced; and advanced. Each level has ten sections through which the students can practice the language in various ways (see Figure 1). While the main focus of the program is reading, it is designed as an integrated course to fulfill the students’ needs in learning the language. Within each section, there are six sub-sections where students practice different level-appropriate language skills. One nice feature is that each level is represented by a unique color under the main titles and subtitles (shown in Figure 1); it also has an indicator to show the percentage of each strategy that has been finished (visible in the “Progress” bars on the right side of the screen). Another helpful feature is that during work on the activities, students can look up words in the Online Cambridge Dictionary by holding down the Ctrl key and clicking on the word.

Figure 1. Upper intermediate level menu

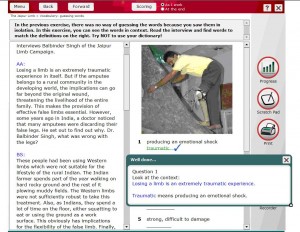

Evidence of the integrated nature of the instruction afforded by Active Reading can be found in the fact that there is a scratch pad (see the right side of Figure 2 below). This feature can be used to write notes when working on the reading activity or for writing activities. Any written notes will be saved in the student’s account and can also be printed out for classroom discussion. Students also have the option to record their own notes by using the recorder that is available under each activity (also shown in Figure 2). These are just a couple of the ways that the program allows for the integration of skills.

Figure 2. Using headings & pictures to help reading

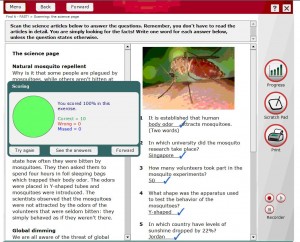

One very important feature of the program is that it is designed to offer feedback to students for each activity (as can be seen in Figures 3, 4, and 5). A score is given and feedback is provided for each answer.

Figure 3. Reading techniques activity with feedback

Figure 4. Vocabulary guessing words activity with feedback

Figure 5. Scanning the science page article activity with feedback

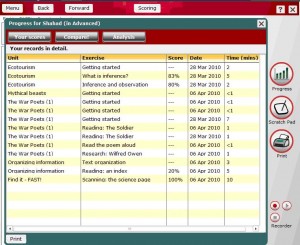

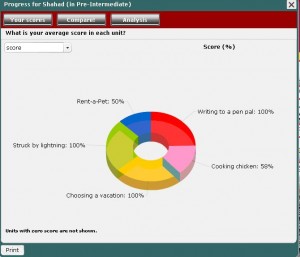

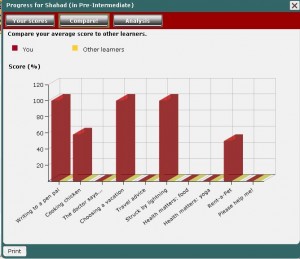

The students also can get a report at any point during the course by clicking on the “progress” button that is available on all screens (see Figures 6, 7, and 8). In addition, the program issues a certificate at the end of each level which provides complete feedback. Besides the benefit of offering feedback to students, the certificate encourages them to participate in another level.

Figure 6. Detailed report for the advanced level

Figure 7. Average score for each unit in the pre-intermediate level

Figure 8. Comparing average scores to other learners

Evaluation

Providing cognitive challenge and opportunities for deep processing of meaning

There are many opportunities for students to challenge themselves and get deep understanding of the meaning throughout the activities in the Active Reading program. In one example, the students have opportunities to think deeply about topic sentences and then make predictions about what each text will be about. In this example, the students write a paragraph for each topic sentence using the scratch pad or print the page and write their own notes to share with others in class.

Proofreading is another good example of a cognitive challenge; in Active Reading students read essays about different issues that contain mistakes. After reading the essay, the students need to find the errors in the text by clicking on them (the number of errors is given in the instructions). Feedback is given immediately, which means that the students have to think deeply before clicking on the wrong word in order to obtain a high score.

These are just a few examples of how this program provides cognitive challenges and opportunities for deep processing of language.

Relating instruction to prior knowledge and experiences

Cummins, Brown & Sayers (2007) argue that “prior knowledge, skills, beliefs, and concepts significantly influence what learners notice about their environment and how they organize and interpret it” (p. 43). Tasks should be based on the students’ prior knowledge and background to enhance students’ understandings. In the Active Reading program, there are many examples that support this condition. One is the pre-intermediate level activity entitled Using headings to help reading (see Figure 2). In this activity, the students are given some headlines from a newspaper and they are required to figure out the meanings using their background knowledge. Such an activity will help students connect ideas from their background to the headings and pictures in order to develop a framework for understanding the text. The students can also get some help from the examples given at the beginning of the task. Many such prior knowledge connections can be found within the different levels and activities in the Active Reading program.

Promoting active self-regulated collaborative inquiry

It is very important that students should be given a chance to take control of their learning and be active in the learning process. This helps students gain a clear understanding of the process and develop their own knowledge. One example that meets this criterion can be found in Unit Four of the intermediate level of Active Reading. In this task, the students have opportunities to read about using email and text messages. The worksheet attached at the end of this activity can serve as the basis for valuable discussions with classmates. The students can practice these activities in a group and come up with answers or solutions collaboratively.

Promoting affective involvement and identity investment

In Active Reading one activity encourages students to write a letter to introduce him/herself to a pen pal in another country. Students can practice their new language and involve themselves deeply in coming to know about other cultures. This activity allows students to invest in their identities as multilingual, international people, and this should lead to better learning outcomes.

Encouraging extensive engaged reading and writing

There are many activities in Active Reading that aim to engage students in active and extensive reading followed by writing. These activities encourage students to think and read other sources for more details about a topic. Most of the readings are connected to the writing so students can improve these skills in an integrated way. In addition, in the pre-advanced level, the students can develop prediction skills, learn about organization in different kinds of texts, read for details, headings and topic sentences, and understand contrast in a text. Worksheets and external links involve learners in deeply exploring these and other reading and writing activities.

Developing strategies for effective reading, writing, and learning

Learners need to know how to use a variety of strategies for language learning and use, and they also need to be able to choose the right technique at the right time. Active Reading provides learners with different kinds of activities that meet this challenge; strategy instruction is integrated with the activities in different units. For example, students learn reading strategies such as scanning, skimming, reading for information, and making notes. These strategies are followed by related activities that enable students to practice their understanding. Practice with strategies for writing can also be found in Active Reading. Learners have the opportunity to learn and use writing strategies that are appropriate for their level.

Conclusion

While there is much to like about Active Reading, a few things could be improved in future versions.

- Recording voices can be invaluable if the recording can be saved and then reviewed by teachers for evaluation and feedback or can be shared with peers.

- Most of the videos in the program are recorded by one or two persons; however, using different people from different backgrounds would enrich the content. Moreover, using authentic videos related to the topic would be interesting and engaging to students.

- Although the external links in the program are generally useful, they can be a source of frustration if they do not work properly. For example, in the elementary level Unit 3, there is a broken link (ebooks). This sort of problem can be a shortcoming when using the CD version of the program, so it would be good to find a way to provide updates to customers who have purchased the CD.

All in all, Active Reading is a useful program that goes a long way toward meeting the criteria described by Cummins, Brown, and Sayers (2007) and conditions for classroom language learning (Egbert, 2005, pp. 6-7). It does an especially admirable job of providing meaningful feedback to students, and it provides an abundance of reading materials. At the end of the course, students can get a certificate that shows their progress. Another good feature is that a written transcription is always available along with the listening part as an option to help learners who have difficulties in understanding the spoken language. In short, the program holds promise for improving students’ reading ability in English.

References

Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Cummins, J., Brown, K., & Sayers, D. (2007). Literacy, technology, and diversity: Teaching for success in changing times. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Donovan, M. S., & Bransford, J. D. (2005). How students learn. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Egbert, J. (2005). CALL essentials. Alexandria,VA: TESOL Publications.

Judge, S., Puckett, K., & Bell, S. (2006). Closing the digital divide: Update from the early childhood longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Research, 100(1), 52-60.

Lovell, M., and Phillips, L. (2009). Commercial software programs approved for teaching reading and writing in the primary grades: Another sobering reality. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 42(2), 197-216.

About the Reviewer

Omran Akasha is a PhD student in Language and Literacy Education in the Department of Teaching and Learning at Washington State University. He holds a Masters degree in Computing from the University of Bradford and a Masters degree in Translation from the University of Salford, UK. His Bachelor of Arts was in English Teaching from the University of Sebha, Libya. He also worked as an EFL teacher at the university for several years. His main interest is CALL & EFL. The reviewer can be contacted at:

<okshi69 hotmail.com>

hotmail.com>

| © Copyright rests with authors. Please cite TESL-EJ appropriately. |